The tifinagh / Berber alphabet: history and current status

We'll try to trace the history of tifinagh and its evolution, and look at its various forms, including the Ircam, which represents its adapted form. We will also look at the current sociolinguistic status of tifinagh/tifinaɣ in the various countries of the Berber world.

1- Tifinagh, a historical overview

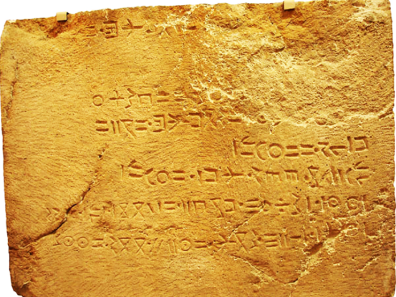

Tifinagh/tifinaɣ is an ancient writing system used by the Numidians in North Africa since ancient times. Also known as Libyan, this alphabet has survived and come down to us through the indigenous inhabitants of this vast region, who have continued to use it. Through a large number of surviving inscriptions (e.g. fig.1), useful information about the language has been revealed, affirming that these ancient forms evolved into the present-day tifinagh (Camps, 1992).

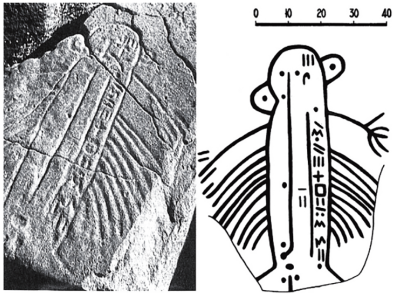

The origins of tifinagh are still unclear. Casajus (2013) believes that the Libyans created their writing system between the 6th and 4th centuries BC (Fig. 1), using several of the letters used by the Phoenicians and Punics at the time and creating others. Amara (2020: 541) speaks of a gap of several centuries in the estimation of ancient Libyan scripts. She cites the Azib n'Ikkis parietal inscription from Yagour (Fig. 2) discovered in the Moroccan High Atlas by Malhomme in 1959, which was dated to Bronze Age II.

.

The use of Tifinagh in North Africa goes back at least as far as the end of the ancient world, when the first writing civilizations appeared (Chaker: 2011). Despite its disappearance in the northern zone of the Berber world for religious reasons[1], its use has continued among the Tuaregs, who consider it to be their people's alphabet, distinguishing them from the Arabs and other neighboring populations (Chaker: 2011).

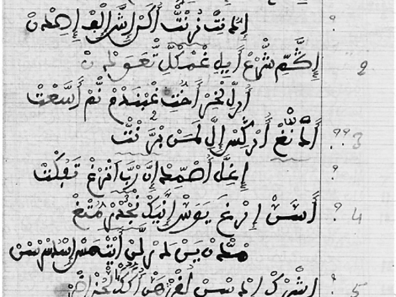

Another aspect of research bears witness to the fact that Berber was written using the Arabic character. This tradition was more widespread in the Souss region of southern Morocco, as evidenced by the manuscripts studied (fig. 3) from this area (Bounfour: 2010). At the end of the 19th century, with the appearance of Jean-Michel de Venture de Paradis's first Kabyle-French dictionary, a new era began with the transcription of Berber into Latin script, which has never stopped to this day. Indeed, much of the scientific research on Berber is carried out in Latin script, and the language itself is taught in Latin script in a large number of universities in Europe and the Maghreb offering a Berber course.

.

2- Evolution, different forms

Ancient Tifinagh/Libyan occupied an immense territory, as signs of this script have been found in the present-day Berber era stretching from the Mediterranean to southern Niger and from the Canary Islands to Siwa in Egypt.

Researchers distinguish four historical ages placing Tifinagh writing in the continuity of Libyan signs. There are four main types of alphabet: eastern and western Libyan, ancient tifinagh and recent tifinagh (Chaker, 1984).

2.1- Eastern and western Libyan

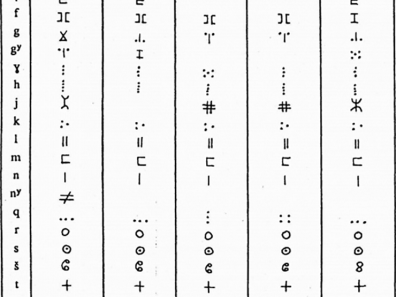

Tifinagh is a consonant alphabet that has continued to evolve throughout history, while remaining morphologically and structurally constant. In the 24-sign Libyan script (Fig. 4), vowels are not transcribed, unlike semi-vowels (y, w), and consonant doubling and tension indication are ignored (Camps :2011).

2.2- From ancient to modern Tifinagh among the Tuareg

In general terms, ancient Tifinagh is considered to be very close to the modern Tifinagh of Ahaggar (Algeria) and Ajjer (Algeria/Libya) (Claudot Award: 2011), and today's Tuareg are able to read and interpret it.

In fact, it's the Tuaregs who have continued to use Tifinagh, and it's thanks to them that this alphabet has survived to the present day. There are slight differences from one region to another (Fig. 5a), but even so, texts written in one region can be easily read and understood in another. On the other hand, tifinagh characters were used to decorate both women's jewelry and men's weapons, as well as to write short texts and love poems.

.

2.3- The Ircam tifinagh[2]: which character for which language?

The sociolinguistic situation in the Berber world has given rise to a fragmentation of dialects and sub-dialects. It was legitimate to reflect on strategies to remedy the precarious situation in which it finds itself and to ensure its survival (Boumalk, 2009), and thus ensure that the Berber language acquires new functions as a written language.

In this context, development interventions in the various Berber countries are part of the picture. This development concerns various aspects of the language, including the characters used in its writing. In this respect, it should be noted that these linguistic interventions, whether official or emanating from organizations or groups of independent researchers, have not accorded the same place to the Tifinagh alphabet as to the Berber language, and that the choice of writing Berber has been based on pragmatic and functional criteria.

For the standardization of tifinagh in Morocco, the Ircam (Institut royal de la culture amazighe) has set up a writing system called tifinagh-Ircam (Fig. 5b) using both ancient script and contemporary innovation.

To achieve this, four criteria were taken into account namely historicity, simplicity, univocity of the sign and economy (Lguensat: 2011). Its development has enabled a simple and exhaustive notation of Berber, at least in the Moroccan linguistic context.

3- Tifinagh and its current sociolinguistic situation

The Berber language is still in a minority and its sociolinguistic status is unfavorable. This situation has a direct impact on its dissemination and transmission (Boukous, 2012). Its linguistic reality is characterized by variation and dynamics. It is broken down into several major regional dialects, each of which is broken down into sub-dialects or local dialects constituting parlers. For example, the regional dialect "Tamazight[3]" contains a number of sub-dialects, including Tamazight from Béni-Mellal, Tamazight from Errachidia, Tamazight from Ait Sadden, etc. (Nejme and Boulaknadel, 2012). Intercomprehension between these dialects is sometimes difficult, especially in remote areas (Boukous, 2012). The process of dialectalization[4] makes a major contribution to the sealing off of isolated and compartmentalized sociolinguistic communities.

It follows from this that the situation of tifinagh is not the same in all Berber countries. It depends on the sociolinguistic status of Berber in general. In this sense, we need to distinguish between states where Berber is an official language and other countries where it is not recognized as a language with official status. To illustrate this disparity, let's take the following examples: Morocco, Algeria. In this respect, Morocco stands out for the fact that Tifinagh has not only been developed and codified, but also made official by the organic law promulgated in 2019[5], which stipulates that it is the only typeface used to write the standard Berber language in education, in administrations, on posters and in everything else relating to the public sphere. While the status of tifinagh in Moroccan language policy is relatively clear, it is less so in Algeria. In the absence of an official text, the use of Tifinagh is not yet a matter for the State. In terms of usage, we can distinguish two phases. The first concerns the use of tifinagh in associations, by activists or in the arts and crafts. In all these cases, its use is limited to the private sphere. In the second phase, the use of tifinagh expanded to touch on various aspects of public life. Here, it is not a matter of choice, but rather of official policy.

In what follows, we will describe the status and use of tifinagh in certain areas, comparing it with other Berber writing systems.

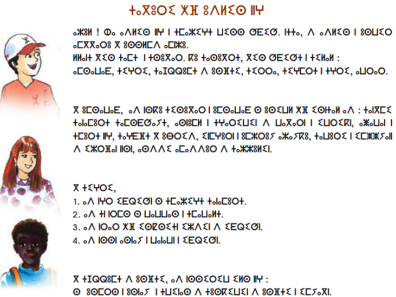

3.1- The use of Tifinagh in teaching

Let's remember that Berber is taught regularly and officially in three countries: Morocco, Algeria and Libya. In Morocco and Libya, Berber is taught exclusively in Tifinagh. Hence the textbooks and teaching aids produced using these characters (Fig. 6a, 6b, 6c, 6d). In Morocco, these are produced under the supervision of Ircam.

In Morocco, tifinagh is currently only used in primary schools. It is not used alone at university. It is used in the rare courses devoted to Berber writing as a language of instruction. In Algeria, the Latin alphabet is used instead of Tifinagh for teaching purposes.

3.2- Tifinagh in literature

The majority of literary works are written in the Latin alphabet. Writers consider that their work will be much more widely read if they use this alphabet. The readership has already become accustomed to these characters, which are universal, and therefore not all readers will make the extra effort to learn Tifinagh, which is still not taught in all schools, whether in Morocco or Algeria.

In addition, we note the presence of associations that encourage literary production, particularly among young people, using the Latin alphabet; this is the case, for example, of the Tirra foundation in the southern region of Morocco. The presence of the Latin alphabet to the detriment of Tifinagh can be justified by the fact that literary creation in most cases escapes official state policy, particularly in Morocco. On the other hand, literary productions financed or published by Ircam are written in tifinagh (novels, literary productions for children or poems). In addition, the use of Arabic characters is limited to a small number of literary works. It should be pointed out that the choice of one or other alphabet is often ideologically motivated, particularly the choice of Arabic script.

3.3- Tifinagh in the social landscape

In many cases, the use of the tifinagh alphabet has an identity-related aspect. It's a form of resistance and militancy. For this reason, activists and defenders of Berber culture ensure that the titles of posters, banners and all papers intended for the general public use tifinagh, and that it occupies the central place it deserves in relation to other languages, particularly Arabic and French. This is a symbolic act aimed at asserting the use of Berber (with its tifinagh alphabet) by the general public, but above all by the official authorities.

Tifinagh has also become one of the symbols of the Berber movement[6], enabling it to strengthen its presence in demonstrations and all forms of protest by different socio-professional categories.

In recent years, tifinagh has been used in the writing of slogans, banners and on all posters. In fact, Berber advocates are taking over categorical representations.

Let's take the example of the protests by contract teachers in Morocco. A large proportion of the posters, banners and slogans are written in Berber with the tifinagh characters (Fig. 7a, Fig. 7b).

![Fig. 7a : Manifestation des enseignants contractuels au Maroc[7]](https://www.inalco.fr/sites/default/files/styles/4x3_sm/public/assets/images/tifinagh_-_figure_7a_web_0.png?h=111ff849&itok=b7RigNAa)

![Fig. 7b : Slogans dans une manifestation des enseignants contractuels au Maroc[8]](https://www.inalco.fr/sites/default/files/styles/4x3_sm/public/assets/images/tifinagh_-_figure_7b_web.png?h=3d2b0c77&itok=MEOoryen)

3.4- Tifinagh in the public sphere

Generally speaking, in Morocco as in Libya, the presence of tifinagh is regaining more and more ground. And even if the Moroccan authorities have not yet promulgated the organic law postulating the use of Berber in public or private administrations, tifinagh is present in certain official papers, in the titles and names of ministries, in the premises of administrations, on road signs etc. (Fig. 8a, Fig. 8b).

As for Libya, the Berber regions have given themselves autonomy over the linguistic question, in the territories where it is a mother tongue.

3.5- Tifinagh in new technologies, social networks and the media

Since the early 2000s, Ircam and a number of researchers and activists have made it their mission to introduce Tifinagh into the various fields associated with the digital world. Efforts have been made to adapt Tifinagh to the computer system, introducing it into keyboards, translation and conjugation applications and websites. Much of the work has been done by Ircam.

In addition, and since the advent of social networks, we've noticed an investment in the dissemination of tifinagh. In the vast majority of cases, its use is seen as an act of militancy. This takes different forms: dedicating discussion groups to writing in Tifinagh, using Tifinagh in the writing of user profiles, particularly on Facebook, and dedicating pages and groups to learning Amazigh with the Tifinagh alphabet.

In most audiovisual media, Tifinagh is not used systematically. Its use is limited to certain programs or advertisements. On the other hand, in Morocco and Libya, there are channels that use tifinagh as the official Berber script.

Ancient Berber manuscripts bear witness to the history of tifinagh writing, which dates back to at least the fourth century B.C. This script survived for centuries, especially among the Tuareg. Its adaptation to the current sociolinguistic situation began with militant movements defending the Berber cause in the late 1970s, before it was officially adopted as a Berber script, first by Morocco and a little later by Libya. The linguistic landscape of Maghreb countries, particularly in Morocco, bears witness to the return of tifinagh to reclaim its rightful place after a long predominance of Arabic and Latin alphabets.

El Mustapha BARQACH and Driss RABIH

El Mustapha BARQACH, Chargé de cours at Inalco in didactics of languages. Specialist in Berber didactics.

Driss RABIH, PhD student at Lacnad on "Berber phraseological units: motivation and etymology".

Bibliography

Aghali-Zakara M., (1984) "Vous avez dit "touareg" et "tifinagh"?", Bull, des Études Africaines de l'Inalco, n° 7, 13-20.

Boukous, A. (2012). Revitalization of the Amazigh language: challenges, issues and strategies, Institut royal de la culture amazighe (Ircam), Rabat.

Boumalk, A. (2009). "Conditions de réussite d'un aménagement efficient de l'amazigh", Asinag, 3, 2009, PP. 53-61

BOUNFOUR A., " Manuscrits berbères (en caractères arabes) ", Encyclopédie berbère [En ligne], 30 | 2010, document M34a, uploaded September 22, 2020, accessed September 01, 2021.

URL: http://journals.openedition.org/encyclopedieberbere/448

Camps G. (1992), Documents and cultural filters: a propos de la faune néolithique et protohistorique de l'Afrique du Nord, in: The limitations of archaeological knowledge, Shay T., Clottes J. (Dir.), Liège, Université - Service de Préhistoire, p. 211-224 (Etudes et recherches archéologiques de l'université de Liège; 49).

Camps G., Claudot-Hawad H., Chaker S. and Abrous D., "Écriture", Encyclopédie berbère [En ligne], 17 | 1996, document E03, online June 01, 2011, accessed August 25, 2021.

URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/encyclopedieberbere.2125

CHAKER S., (1984) Texts in Berber Linguistics, CNRS, Marseille.

CHAKER S., (2011). L'écriture libyco-berbère. État des lieux et perspectives. https://www.centrederechercheberbere.fr/lecriture-libyco-berbere.html. Accessed 05/09/2021.

CASAJUS Dominique, "Sur l'origine de l'écriture libyque. Quelques propositions", Afriques [On line], Débats et lectures, online June 04, 2013, accessed September 16, 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/afriques/1203

LGUENSAT M., (2011), Aménagement graphique de tifinagh. Questions relating to cursive adaptation and visual optimization of the Amazigh script. Including cursive, stylized cursive and semi-cursive proposals for the tifinagh system. Ircam.

Nejme, F.Z, Boulaknadel, S. (2012). Formalization of standard Amazigh with NOOJ, JEP-TALN-RECITAL 2012, Atelier Talaf 2012: Traitement automatique des langues africaines, PP. 85-95.

Ouiza AIT AMARA (2020), L'épigraphie libyque et son apport à la connaissance de la société numide, in L'epigrafia del Nord Africa : novità, riletture, nuove sintesi, a cura di Samir Aounallah, Attilio Mastino, p. 537-557.

Royaume du Maroc, Bulletin Officiel N° 6816 en date de 26-09-2019, URL : http://www.sgg.gov.ma/Portals/1/BO/2019/BO_6816_Ar.pdf?ver=2019-10-01-155752-407 (accessed on 19/09/2021, at 17:30).

Notes

[1] This region was Islamized by the Arabs in the 8th century.

[2] Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe.

[3] This is one of the major regional variants of the Berber language in Morocco. It is particularly widespread in the Middle Atlas in central Morocco.

[4] The historical process by which a language, originally homogeneous or little differentiated, takes on increasingly differentiated forms in the geographical area where it is used (e.g. Latin, which breaks up to give rise to the various Romance languages). Larousse.

[5] The organic law n°26.16 defining the process of implementing the official character of Berber, the modalities of its integration in education and in the priority areas of public life was published in the Bulletin officiel n°9314, of September 26, 2019.

[6] This is a movement represented by a group of associations, intellectuals and activists from different backgrounds. They all share a discourse whose main objective is to defend Berber in all its dimensions: linguistic, cultural, historical, identity.

[7] aswatdriouch.com, accessed on 19/09/20121, at 16 : 43.

[8] amadalamazigh.press.ma, accessed on 19/09/20121, at 18 : 21.

[9] Photo from the news website: maghrebvoices.com,

accessed on 19/09/2021 at 18 : 57.