The salar

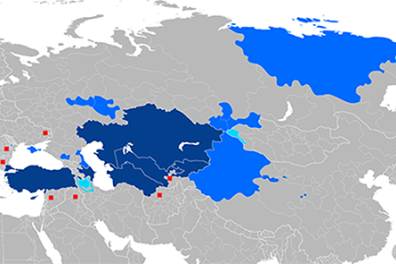

The latter is itself divided into two dialects, which differ from each other mainly in certain aspects of their phonology. After long being regarded as a dialect of the Karluk language now known as Uyghur, there now seems to be a consensus that Salar is Oghuz. It should be pointed out, however, that Salar has a number of features that are difficult to explain other than as the result of the influence of non-Oghuz Turkish dialects.

As for Yoghur (in Yoghur: yoğur söz), also known as Sarïgh Yoghur, or, literally, "yellow Uyghur", or as Western Yoghur, it is a Turkic dialect from China most likely belonging to the Siberian group. It is spoken mainly in the autonomous Yoghur county of Sunan, in the central part of Gansu province. Its speakers, who number around 4600, form part of the Yoghours, an ethnic community of approximately 14,000 people professing Lamaic Buddhism and divided into three linguistically. In addition to those who speak the variety of Turkish we're interested in here, there are two other groups: one comprising around 2,800 people who speak Yoghor, a Mongolian dialect, and the other, the majority, made up of monolingual Chinese speakers.

There is much evidence to suggest that the Yoghours are descended from the Uyghurs proper (not to be confused with the Uyghurs of Xinjiang, who chose to call themselves such only at the beginning of the 20th century), a branch of the Turks who played an important role in Upper Asia in the Middle Ages, and whose culture influenced to varying degrees not only other Turkic groups, but also the Mongols, who owe them their principal traditional writing system.

The Salars, custodians of the language we are interested in, are predominantly Sunni Muslims of Hanafi rite, but various Sufi currents spread among them between the 17th and 19th centuries, and the early 20th century saw the Ikhwân movement take root in Xunhua.

Historical sources on the Salars attest to their presence in the region where most of them still live today, namely the upper reaches of the Yellow River, in the east of what corresponds to today's Qinghai province and southern Gansu, as early as the end of the 14th century or, more precisely, 1370. There is also another tradition, according to which their arrival in the area in question would have taken place earlier, dating back at least to the previous century, at the time of Mongol domination, of which the Salars would have been auxiliaries. In any case, we have no precise data on either their migration or their settlement. The Salar oral tradition, however, goes some way towards filling this gap. In fact, the Salars still remember their community's Central Asian origins, with the most common version of the "ethnogenetic" narrative locating the starting point of their ancestors' journey in the vicinity of Samarkand.

According to figures from the 2010 Chinese general census (the latest published), the Salar population numbers 130,607, of whom, according to other, unofficial data, some 87,000 live in Xunhua. Most Salars are Salar-speaking.

Salar has a traditional writing system called türk oğuş, which is an adaptation of the Arabic alphabet, and is now known only to a few elderly people, and has been the subject of very few studies, including two articles, one by Hán Jiànyè (1989), which this researcher published under the name Yībùlā Kèlìmù, and the other, recently published, by the author of these lines (2020). The description of the language of texts written in türk oğuş, which differs in many respects from today's ordinary salar, remains entirely to be done.

Because of the framework allotted for this presentation, we have confined ourselves below to presenting a few points of morphology. Readers wishing to learn more about the salar will find further information in the documents listed in the bibliography.

1. Derivation

1.1. Suffixes used to form denominative nouns

-cI : ağaşcı "woodcutter" < ağaş "wood", satıḫcı "trader" < satıḫ "sale, trade"; -lıḫ ~ -liḫ ~ -luḫ ~ -lüḫ, : otluḫ "meadow" < ot "grass", tütünlüḫ "chimney" < tütün "smoke", yağmurluḫ "umbrella" < yağmur "rain"; -cin : purnaḫcin "snot" < purnaḫ "snot", gaçıcin "talkative" < gaçı "speech".

1.2. Suffixes used to form denominative verbs

-lA : derle- "sweat" < der "sweat", yırla- "sing" < yır "song", yüḫle- "load" < yüḫ "burden"; -sA : oḫusa "to be sleepy" < oḫu "sleep", susa-"to be thirsty" < su "water".

1.3. Suffixes used to form deverbative nouns

-Im (sometimes -(U)m after a syllable containing a rounded vowel): bilim "knowledge" < bil-"know", ülim ~ ölüm "death" < ül- ~ öl- "die".

-(V)n: tütün "smoke" < tüt- "to smoke (intransitive)", eḫin "cultivation" < eḫ- "to plant";

-mA (sometimes -mI): yeme ~ neme ~ nemi "food" < ye- "to eat".

1.4. Suffixes used to form deverbative verbs

1.1.1. Voice suffixes

1.1.1.1. Suffixes used to put certain verbs into the passive voice

-(V)l ~ -ıl: açıl- "to open" < aç- ~ aş- "to open", bilil- "to know oneself" < bil- "to know".

1.1.1.2. Suffixes used to put verbs into factive voice

-D(V)r ~ -dIr : bildir- "make know" < bil- "know", ettir- ~ etdir- "make do" < et- "do",

iştir- ~ işdir- "make drink" < iş- "drink", vaḫtur ~ vaḫtır ~ vaḫdır "show" < vaḫ- "look".

-ar ~ -ır : çıḫar- ~ çıḫır- "to bring out", "to extract" < çıḫ- "to get out".

-(V)t: ḫorğat- "to frighten" < ḫorğa- "to be afraid".

>1.1.1.3. Suffix used to put the verb in the reciprocal voice

-(V)ş : uruş- "to hit each other", "to beat each other" < ur- "to hit", "to beat".

1.1.2. Negation suffix -mA~ -ma

It is used to form the negation of most verbal forms.

gelme- ~ gelma- "not to come" < gel- "to come", varma- "not to go" < var- "to go".

2. Nominal inflection

The noun can be affected by plural, possessive and case marks. Plural, possessive and case marks are attached to the noun in the order plural-possessive-case or possessive-plural-case, the second sequence being, as far as we've been able to ascertain, much more frequent than the first.

2.1. The plural

This number is expressed by means of a suffix in the form -lAr: analar "girls" < ana "daughter", kişler "people" < kiş "person".

2.2. Possessive affixes

Historically, they are a series of suffix-form variants of genitive personal pronouns.

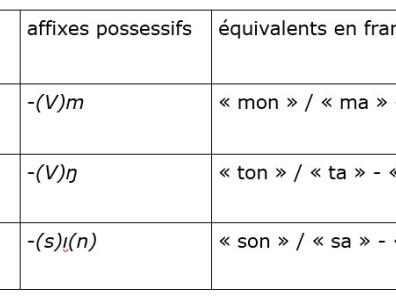

Salar has three possessive affixes. The paradigm they constitute is as follows:

Examples: belim "my waist" ~ "our waist" < bel "waist", anam "my daughter" ~ "our daughter" < ana "daughter", başıŋ"your head" ~ "your head" < baş "head", Golı "his arm" ~ "their arm" < Gol "arm".

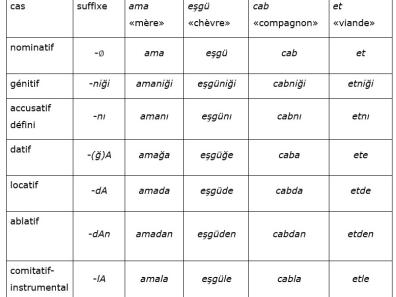

2.3. Cases

The noun salar can take seven case suffixes. These appear as in the table below:

Adrien Alp Vaillant

Doctor at Inalco, associate member of CETOBAC

Bibliography

Dwyer (Arienne), Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, part 1: Phonology, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 2007.

Dwyer (Arienne), "The Turkic Stata of Salar: an Oghuz in Chaghatay clothes?", Turkic languages 2, pp. 49-83, 1998.

Hán (Jiànyè) 韓建業 (under the name Yībùlā Kèlìmù 依布拉-克力木), "Tán lìshǐshàng de sālāwén - tǔěrkèwén"談歷史上的撒拉文-土爾克文 (From the "Turkish script" [= türk oğuş], the historical salare script), Yǔyán yǔ fānyì語言與翻譯, vol. 3, 1989, p. 1-4.

Hán (Jiànyè) 韓建業, Mǎ (Chéngjùn) 馬成俊, Sāwéihàn cídiǎn撒維漢詞典 (Salar-Uyghur-Chinese Dictionary), Mínzú chūbǎnshè 民族出版社, 2010.

Lín (Liányún) 林蓮雲, Sālāyǔ jiǎnzhì 撒拉語簡誌 (Salar sketch), Beijing, Mínzú

chūbǎnshè民族出版社, 1985.

Lín (Liányún) 林蓮雲, Sālā hàn hàn sālā cíhuì 撒拉漢漢撒拉詞彙 (Lexique salar-chinois

Chinese-Salarian), Chengdu, Sìchuān mínzú chūbǎnshè 四川民族出版社, 1992.

Mǎ (Weǐ) 馬偉, Stuart (Kevin), the Folklore of China's islamic Salar nationality, Lewiston

NY: E. Mellen Press, 2001.

Tenichev (Edkhem Rakhimovitch), Salarskie teksty (Salar Texts), Moscow, Akademija nauk SSSR, Institut jazykoznanija, 1964.

Tenichev (Edkhem Rakhimovitch), Stroj salarskogo jazyka (Structure of the Salare language),

Moscow, Akademija nauk SSSR, Institut jazykoznanija, 1976.

Vaillant (Adrien Alp), Une langue en voie de disparition : le salar au sein de la turcophonie,

unpublished doctoral thesis, doctoral school: Languages, Literatures and Societies of the World,

ED 265, Institut Nationale des Langues et Civilisations Orientales, Paris, 2017.

Vaillant (Adrien Alp), Essai de lexique salar-français, Paris, l'Harmattan, 2019.

Vaillant (Adrien Alp), Présentation et esquisse de description de l'écriture traditionnelle

salare or türk oğuş, Turcica, no 51, 2020.