The Forest of Brushes - Chinese Calligraphy

Artists, scholars, critics and statesmen have elevated it to levels rarely reached in the history of civilization. Intimately linked to writing, an instrument of divination, power, unification and culture, calligraphy emerges from the tip of the brush that never leaves the hand of the Chinese official, military leader, writer, scholar or painter, and these are the calligraphers. The ingredients of the various practices are shared by all: water, ink, an inkwell, and silk or paper.

Chinese calligraphy simultaneously brings into play, with a remarkable economy of means, several facets of human behavior to which it gives an aesthetic pleasure not found in any other form of expression. In fact, calligraphy operates on both the poetic level, by manipulating the semantic charge of writing, and the visual level, by producing forms. To this should be added the physical dimension, as calligraphy is also a choreography of the movement of fingers, wrists, arms and the whole body. A highly personal spiritual exercise of rare density, it provides the calligrapher and the enlightened spectator with an intense aesthetic experience shared by tens of millions of Far Eastern enthusiasts (China, Japan, Korea) for many generations.

Often awkwardly compared to "abstract" art, calligraphy is increasingly attracting the attention of Westerners, who rightly see in it a community of values that their own twentieth-century practices now make more accessible.

Chinese calligraphy can be divided into two main stylistic families:

1. regular calligraphy: I) bone and carapace writing, II) "grand-sigillary" calligraphy, III) "petit-sigillary" calligraphy, IV) "scribe" calligraphy, V) "regular" calligraphy.

2. cursive calligraphies: VI) "common" calligraphies, VII) "cursive" calligraphies.

The brief overview below takes up this distinction and briefly presents the history of the styles that make up these two major groups.

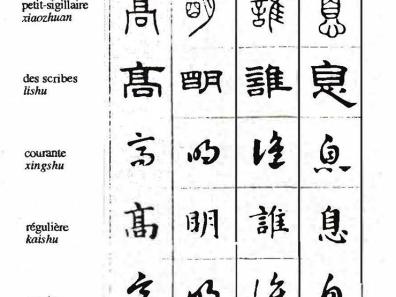

The fig. 1 illustrates the calligraphy in five different styles of four Chinese characters, and gives a first idea of the diversity of possible forms when one takes into account the impressive quantity of Chinese characters listed (there are around 54,000 of them - including 7,000 in common use - in the Grand Dictionnaire de la langue chinoise, Hanyu da zidian, published in 1986).

1. Regular styles

Bone and carapace writing - 甲骨文

It is to legendary figures from the time of the Yellow Emperor such as Ju Song and Cang Jie that Chinese mythology attributes the invention of writing. Endowed with two pairs of eyes, Cang Jie is said to have observed the constellations in the sky and the imprints left by birds on the ground; he then came up with the idea of a writing system designed to replace the archaic forms of notation that consisted of tying knots on cords and notches on sticks in order to "keep in memory" the ten thousand facts and things.

The earliest known forms of a Chinese writing system are the jiaguwen, "writing on bones and shells", primarily intended for divinatory practices. These show aesthetic preoccupations that foreshadow those of future calligraphers. The Shang (16th century B.C. - 1066 B.C.) and Zhou (1066 - 221 B.C.) scribes were familiar with a form of brush with which they sometimes marked characters that were then engraved on supports such as deer or bovid bones or tortoise shells. This brush is an offshoot of the potter's brush, which has been used since Neolithic times to mark and decorate clay products. Using their archaic instruments, scribes of jiaguwen characters strive to respect a relative standardization of writing and its graphic specificities: order and relative dimension of strokes, character composition. There are carapaces and bones that served as "practice tablets" on which characters traced regularly - by a master - are "copied" more clumsily by an apprentice. The complexity of this writing implies older forms that we don't yet know about.

It was at the end of the Qing dynasty (1644 - 1911) that writing specialists began to take an interest in these materials, which peasants occasionally unearthed in the course of their agricultural work and which were then sold in Chinese stalls under the name of "dragon bones"; these were intended to be ground into powder and used in pharmaceutical compositions to treat malaria.

Systematic excavations began in 1928 at the Shang site of Xiaotun; later, other sites revealed bones and shells with distinctly different scripts, and to date over 60,000 specimens have been observed by researchers, who have managed to record over 5,000 different characters, more than two-thirds of which have been translated[2]. Their discovery has also given rise to new practices among twentieth-century Chinese calligraphers, many of whom have tried their hand at brush reproductions of these ancient scripts, which have now found their way onto formats not originally intended for them, such as vertical and horizontal scrolls, steles and colophons accompanying paintings, to name but a few examples.

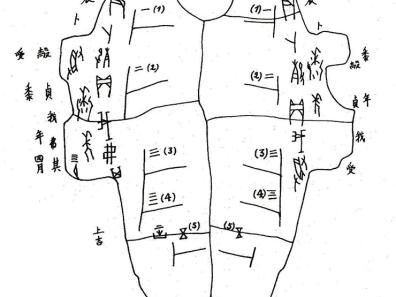

We reproduce fig. 2 a divinatory carapace from the Yin period which features twice two vertical columns of symmetrical inscriptions corresponding to a request about a millet harvest. Transcriptions of the characters in modern script are given on the outside of the shell's perimeter.

Here's a word-for-word translation:

Right side, left column (7 characters): bing zhen: [to the day] bingzhen - bu: divination - Ke: [the diviner] Ke - zhen: oracle request [about this:] - wo: we - shou: get;

right column (2 characters) shu: millet - nian: year's harvest

("On the day bingzhen, divination. By diviner Ke oracle request on this: will we get a millet harvest?").

Left part, right column (8 characters): bing zhen: [on the day] bingzhen - bu: divination - Ke: [the diviner] Ke - zhen: oracle request [on this:] - wo : we - fu : don't - qi : probably;

left column (3 large characters, 2 small): shou : get - shu : millet - nian: year's harvest - si: four - yue: lunation

("On day bingzhen, divination. By the diviner Ke asks oracle on this: will we then not get the millet harvest? 4th month. "

In the lower left, to the left of the character wu, "5" (part of the diagram numbering) appear the characters shang, "superior" and ji, "pomp" which are the diviner's conclusion ("eminently favorable") as to the coin's analysis[3].

.

Grand-sigillary calligraphy: dazhuan - 大篆

The latest use of jiaguwen dates back to the Western Zhou (1121- 771) when writing took root on another choice medium of Chinese antiquity: bronze. Engraved upside down in the molds of ritual vases, the characters in use at the time usually appeared at the bottom of the vessels; they sometimes constituted relatively long texts intended to be brought to the attention of the gods or ancestors to whose worship the bronze objects were addressed.

These scripts, whose general forms are quite similar to those of the jiaguwen which preceded them, developed in a more or less orderly fashion throughout the Chinese world up until the period of imperial unification of the Qin (221 - 206). They were subsequently referred to by the generic name dazhuan, "great-sigillary" (or "great-seal script", the character zhuan means "to spread", "to propagate" and "seal"), as opposed to the script unified on the order of Qin Shihuang (r. 221 - 210), which came to be known as xiao zhuan, or "little seal" script.

The grand-sigillary script, dazhuan, features rounded and angular shapes at once, their essential feature being the installation of characters in irregular spaces (square, rectangle), they also bear witness to the great diversity of styles and orthographies in use until the end of the Warring Kingdoms period.

The traditional history of Chinese calligraphy attributes the "invention" of the grand-sigillary script to the Great Scribe Shi Zhou (in the service of King Xuan of the Zhou, r. 827 - 781), which is why it is also called Zhoushu, the "Zhou script".

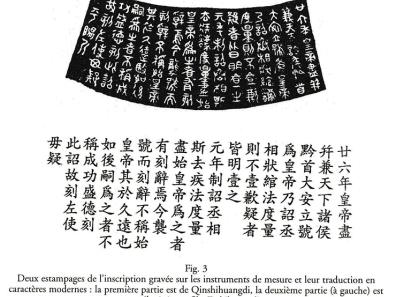

fig. 3 is a reproduction of a large-sigillary inscription on a bronze measure (a one-pound weight) from the Qin period, intended to commemorate the unification of weights and measures promulgated by Emperor Qin Shihuang in 221 BC.C. Beneath the embossing is the transcription in modern regular characters, translated by Édouard Chavannes [4]:

[Text of the promulgation]: "In the twenty-sixth year, the Sovereign Emperor finished uniting all the world in his hand; the lords and the Black Heads enjoyed great calm. He instituted and assumed the title of Sovereign Emperor. He then ordered the Zhuang and Guan advisors to clearly uni fier all the rules, measures of length and capacity and standards which were not identical and which, through their inadequacy, left room for doubt.

[Text by the emperor's son and successor, Er Shihuang]: In the first year, the imperial order was given to councillors Si and Qu: 'The rulers and measures of length and capacity, it was Shi Huangdi who made them all.

They bear engraved inscriptions. Now, although I have succeeded him in his title, the inscriptions I engrave are not equal to those of Shi Huangdi and remain far removed from them. If any of my successors make (inscriptions), let them not equal his perfect glory, his accomplished virtue. Engrave this decree!' That's why we've engraved it on the left, so that there can be no doubt."

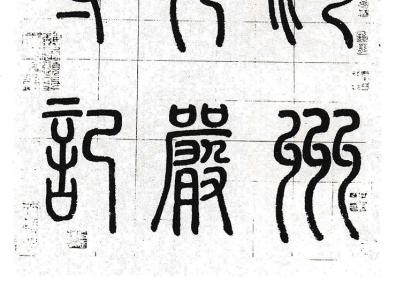

Small-sigillary calligraphy: xiaozhuan - 小篆

The attribution of authorship of the small-sigillary script, xiaozhuan, to the initiative of Li Si, Prime Minister of Emperor Qin Shihuang, is today unanimously accepted. The promulgation of a single, unified and standardized script for the entire Chinese world, in 227 BC, was a political decision of the utmost importance. It would be more than two thousand years before an operation of the same scope was undertaken after the founding of the People's Republic of China, with the implementation of writing reform from 1952[5].

The petit-sigillaire was first and foremost a script at the service of Qin Shihuang's authority. Imposed by the imperial power, it embodied all the political options implemented by the new regime, for whom it served as a propaganda tool. Spread and visible on stone monuments such as steles, but also on the many official documents in circulation, its very regular, standardized, disciplined and unifying forms are a reminder of the unquestionable hegemony of the victor. It wipes the slate clean of diversities and variants (there were, for example, up to fifty forms of the character yang, "sheep", or seventy-six different spellings of the character ren, "man" on the jiaguwen), it discards, once and for all the inequality of dimensions and asymmetry of forms prevalent in previous scripts.

The xiaozhuan character is set in a regular rectangular space, in height, in which its composition balances out; whatever the number of strokes that make it up, it elongates or compresses in order to occupy the uniform space assigned to it, a rule that will know no exceptions until our time.

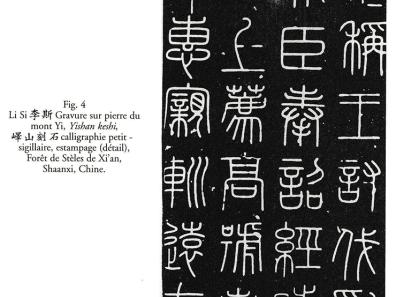

The fig. 4 is a detail of an embossing from the Mount Yi stone engraving, Yishan keshi.

This stele was engraved under the Qin (22 1 - 206 BC.C.), shortly after the promulgation of standardized writing. Premier Li Si is generally credited with the calligraphy of a series of steles engraved and erected during a tour of the empire by the First Emperor Shihuang. The example presented here relates the visit to Mount Yi (Shandong province)[6]; the original stele disappeared under the Tang (618-907), a new stone was engraved from an original stamping under the Ming and then installed in the Xi'an Stele Forest (Shaanxi province).

Progressively falling into disuse in favor of the regular "scribes'" script, lishu, petit-sigillaire was reserved for ornamental purposes and seal engraving. From the Tang onwards, it once again aroused the curiosity of calligraphers, who often reserved it for the frontispiece inscriptions of book titles, paintings or calligraphic pieces.

The fig. 5 represents such an inscription installed at the start of a horizontal scroll of regular calligraphy by the painter Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan dynasty (1279 - 1368).

It features 6 characters (from right to left and top to bottom):

Hu-zhou Miao-yan si ji: Inscription from Miaoyan Temple in Huzhou (word for word: Hu - zhou : [place name] Huzhou; Miao-yan-si: [place name] Miaoyan Temple; ji: inscription).

Scribes' calligraphy: lishu - 隸書/隶书

L'apparition du style d'écriture dit "des scribes" (ou "des chancelleries"), lishu, remonte à la dynastie Qin (221 - 206) ; Traditional history recounts the misadventures of a certain Cheng Miao, who is said to have perfected the new script in the jails of Qin Shihuang, or the exploits of a later Han Wang Cizhong, who reorganized ancient writing, "invented the lishu, transformed himself into a bird and disappeared into the heavens".

In reality, scribal calligraphy is considered to be an offshoot of petit-sigillaire, xiaozhuan, and corresponds to the growing quantitative importance of handwritten documents, which led to the large-scale production of texts written rapidly with a brush on easily accessible supports: wood, bamboo, cloth. It was the work of civil servant scribes (in Chinese: liren) from the Qin onwards that spread the new script, which initially coexisted with the small sigillary, increasingly reserved for solemn uses such as the engraving of steles, before definitively dethroning it under the Han.

Generally speaking, lishu is distinguished by the installation of characters in a horizontal rectangle, by the supported termination of certain descending strokes, which corresponds to the first manifestation of the flexibility of the brush whose stroke can vary in thickness according to the force exerted by the wrist, as well as by the appearance of a series of new strokes: dots (in sigillaries, these are marked by strokes).

In their primitive form, Chinese documents and books took the form of wooden or bamboo tablets bound together in more or less voluminous ligatures. Large quantities of these lamellae were discovered in the oases of north-western China in the early 20th century. Many of them date back to the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD) and are drawn in scribal script, lishu, by accomplished calligraphers like the one reproduced fig. 6, part of a series considered to represent the finest specimens of the style.

The engraved stones and steles constitute another important historical repertoire of the lishu style.

The stela, a detail of which is reproduced fig. 7, is today preserved in the Temple of Confucius in Qufu. It has been admired for its elegant scribal style since ancient times. It features sixteen columns of thirty-six characters each, recounting the circumstances of its erection in 156 AD.C. at the request and expense of an official named Han Chi, who wished to commemorate maintenance work carried out on the site, as well as his donation of ritual vessels for the occasion.

As was the case with sigillary scripts, after having been a style in use to cover the functional needs of writing, (it would be gradually replaced by the regular standard script kaishu from the end of the Han), the scribes' style would be reserved for the use of calligraphers. Many of them practiced producing original, personalized works in scribe calligraphy. A good knowledge of its structure and forms is often part of the training and years of apprenticeship of any accomplished calligrapher.

.

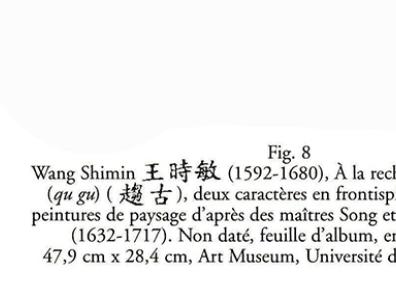

The fig. 8 is a fine example of such an interpretation of the ancient script by the painter-calligrapher Wang Shimin of the late Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644).

Regular calligraphy: kaishu - 楷書/楷书

Regular writing kaishu is the last writing and calligraphy style in the chronological development scheme. It stems directly from the evolution of scribal style, and its main features appear as early as the end of the later Han. However, it wasn't until the Sui (581 - 618) and the early Tang (618 - 906) that the various facets of its evolution became definitively stable.

The regular character (which must show every stroke and point entering into its composition, without exception) is mostly inscribed in a perfect square (more rarely in a rectangle in height), curved graphic elements are replaced by straight or angled lines, and rectilinear forms dominate. The structure of the characters respects a perfectly proportioned balance; this script reached maturity as early as the 4th century and its perfection under the Tang when the great masters Ouyang Xun (557 - 641), Yu Shinan (558 - 638), Chu Suiliang (596 - 658) and later Yan Zhenqing (709 - 785) and Liu Gongquan (778 - 865) gave it its definitive techniques and classical forms. These would remain unchanged until the present day, and would form the matrix for the Chinese characters that printing would spread throughout the Sinicized world from the 10th century onwards. The works of these calligraphers are considered to be veritable monuments of Chinese civilization, and a good knowledge of these different authors is the sine qua non of learning calligraphy.

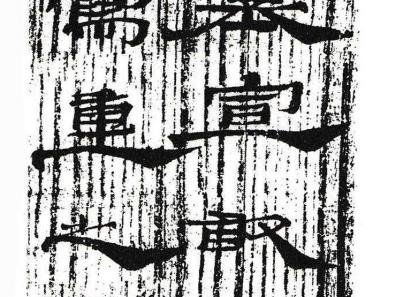

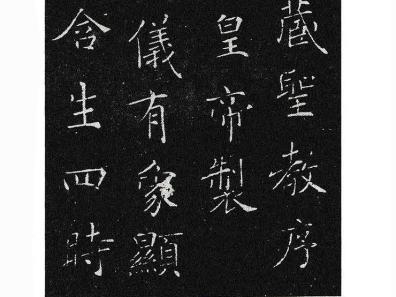

The fig. 9 represents a reproduction of part of an early print of Chu Suiliang's regular calligraphy. The few characters reproduced are part of a set of two engraved steles bearing two texts composed one by Emperor Taizong of the Tang (r. 626 - 649) and the other by his son Emperor Gaozong (r. 649 - 643). These texts were calligraphed by Chu Suiliang and installed during the reign of Empress Wu Zetian (r. 684-704) on the first floor of the Great Goose Pagoda within the precincts of the Da ci'en temple, where the monk Xuan Zang (circa. 596 - 664) completed the translation of the Buddhist canons on his return from India; they can still be found there today.

The seven characters in the first column of Emperor Taizong's text can be distinguished: da Tang san cang shengjiao xu ; word for word: "great [dynasty] Tang three canons [Tripitaka] holy teachings preface" (Preface to the holy teachings of the Tripitaka under the Tang dynasty).

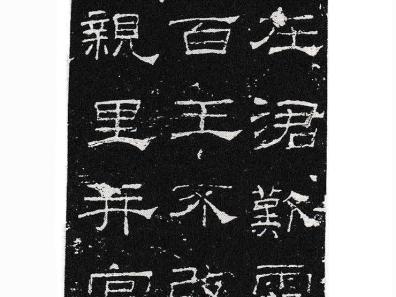

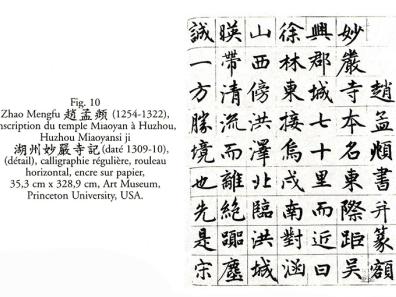

The fig. 10 represents a section of a horizontal scroll calligraphed in regular script by the Yuan painter-calligrapher Zhao Mengfu. The scroll begins at its right-hand end with the frontispiece of fig. 176. This is followed by a short preface, the last sentence of which (Zhao Mengfu shu bing zhuan e :

"Zhao Mengfu calligraphed the frontispiece in sigillaire") can be read in the first column of the reproduction.

From the second column onwards begins the text of the site description proper. Here's a translation:

"The original name of the Miaoyan temple was Dongji. It is located 70 li outside the city of Wuxing. It lies near Xulin. To the east is Wuxu; to the south, Mount Han; to the west [Lake] Hongze; and to the north, [the city of] Hongcheng. A clear stream winds through the surrounding area. [The temple] is away from the noise and dust [of the world]. It really is a wonderful place (...)."

In contemporary times, the use of regular calligraphy has remained very much alive in all manifestations of public and private life when it comes to presenting writing for all to see. The calligraphy of parallel couplets, for example, that are affixed to both sides of doorways on festive occasions, store signs, government and commercial signs, advertising hoardings, company logos, political slogans, building pediments and, above all, book titles, is systematically entrusted to the calligrapher's brush.

The calligrapher's brush is always at the forefront of his or her work.

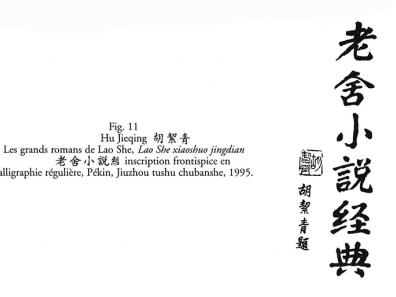

The fig. 11 reproduced the title of a collection dedicated to the great contemporary novelist Lao She (1899 - 1966); this is due to the brushwork of his wife Hu Jieqing.

2. Cursive styles

Common calligraphy: xingshu - 行書/行书

The so-called "common" script and calligraphy, xingshu, are so named because they are in "common" use. Indeed, this style can be said to be the one practiced by hundreds of millions of people who write in Chinese characters in the Far East (China, Korea, Japan). It is the natural script of those who have mastered the written language, during which they were taught the principles and technique of writing the character in its regular form, kaishu.

Faster to execute than the regular, which constitutes its repertoire of forms, current calligraphy links the various strokes within the character, sometimes abbreviating them, characters can be linked together; the brush tip rarely leaves the sheet but the overall appearance and legibility of the text remains intact.

From the point of view of development, the courant style has been present since the beginning of the systematic use of the brush for scribal writing, lishu, in the early Han dynasty.

The first remarkable achievements in courante are generally attributed to Liu Desheng (active 146 - 189) and Zhong You (151 - 230). But it was during the Six Dynasties (220 - 589) that the genius of great masters such as Wang Xizhi (303? - 361) and his son Wang Xianzhi (344 - 388) reached rarely equaled heights in the practice of fluent calligraphy.

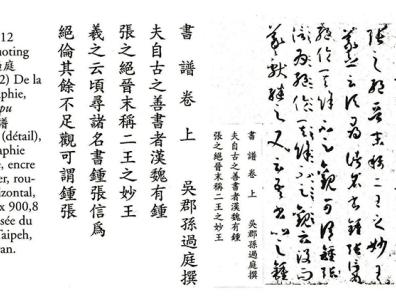

The fig. 12 represents the first lines of a work in fluent calligraphy that is considered an exceptional treasure of Chinese cultural heritage.

Sun Guoting's treatise De la calligraphie, dated 687, is indeed an extremely valuable piece for two reasons: it is a leading authentic autograph work in the style of fluent calligraphy, xingshu; at the same time, it is one of the most famous and important treatises in the history of theoretical texts on calligraphy. The first two characters in the column at the far right of the document are shuand pu, word for word "calligraphy" and "domain", they constitute the title of the piece, which is one of the few original calligraphies from the Tang dynasty (618 - 907) that has come down to us in an excellent state of preservation.

Here's a translation of the first lines of this treatise:

"The best calligraphers since antiquity are Zhong [You] and Zhang [Zhi] of the Han and Wei; they are second to none. The Two Wangs [Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi] of the late Jin are celebrated as prodigies. Wang Xizhi said: "I've just studied the famous calligraphers. Zhong and Zhang are certainly without equal; the others are not worth looking at." It's fair to say that after Zhong and Zhang passed away, [Wang] Xi[zhi] and [Wang] Xian[zhi] became their successors. [Wang Xizhi] also said: 'If you compare my calligraphy with Zhong's and Zhang's, Zhong's is as good as mine, or, as some say, mine exceeds his. Zhang's cao cursive just exceeds mine, but he has perfected [his art through long practice to such an extent] that his ink has blackened a whole pond"

Cursive calligraphy : caoshu - 草書/草书

Pour simplifier, we could say that cursive calligraphy, caoshu, is a rapid graphy - or shorthand - of Chinese writing.

From a formal point of view, the brush technique is the same as that of the fluent and regular; the characters are strongly abbreviated, many strokes are suppressed, ellipsis predominates. Cursive tracings are often the result of a highly accelerated tracing of regular forms. Sometimes the regular tracing order is modified to achieve a comfortable, uninterrupted movement. The main characteristic of cursive is the gestural dimension and highly expressionistic movement it enables the calligrapher to transpose into his composition. It's also worth noting that cursive pieces are often partly illegible, even by specialists, which is why Chinese works on the subject give transcriptions in regular characters alongside hard-to-decipher cursive pieces.

Like regular calligraphy, cursive has been present on Chinese soil since the earliest manifestations of the use of the brush to transcribe writing characters. It is therefore a derivative of all the regular writing styles in use at a given period. Archaeologists have unearthed cursive tracings derived from the great sigillaries, dazhuan, of the Warring Kingdoms (453 - 221). But it wasn't until the later Han dynasty that Chinese calligraphers took hold of the style, raising it over the centuries to astonishing heights as a testament to Chinese artistic genius. It was at this time that a wave of enthusiasm for cursive calligraphy swept across the empire, much to the dismay of a certain Zhao Yi, who took offence to the point of writing "Down with cursive calligraphy! "the first Chinese text devoted exclusively to calligraphy[7], in which he criticizes his contemporaries for "devoting themselves day and night to the practice of 'non-conforming' cursive, caoshu, until they wear out their finger nails and bloody their hands." In his famous diatribe, Zhao takes aim at Zhang Zhi (? - 193? A.D.) by name, considered to be the ancestor of the "Cursor".C.) considered the spiritual ancestor of all Chinese calligraphers.

Three major groups of cursive calligraphy can be distinguished:

-"Old" cursive, zhangcao; the already highly abbreviated characters are not linked together, they are an accelerated writing of the scribes' style, lishu.

- "modern" cursive or simply "cursive", jincao, from the 2nd century AD.C.; characters are often linked together, strokes are evoked by means of dots, abbreviations are systematic, texts, freed from the functional constraints of written communication, are calligraphed for aesthetic pleasure from the end of the 3rd century.

- "Crazy", or "unbridled" cursive, kuangcao, the practice of which spreads from the 8th century onwards; from the Tang (618 - 907) onwards the artistic possibilities of cursive are forcefully demonstrated by artists who practice it with a new, unrestrained freedom. With figures such as Zhang Xu (ca. 700 - 750) and the "mad" monk Huaisu (ca. 735 - 800?) calligraphy reaches extreme forms of personal expression.

The first piece of cursive calligraphy we have today is the Pingfu tie, a letter by the famous poet and theorist Lu Ji (261 - 303) in early cursive, preserved in Beijing's Palace Museum. Cursive characters, mixed with other styles, can be seen drawn naturally, without artifice and in an almost restrained manner, no doubt because the poet was writing a letter to an addressee, without any stated artistic intention.

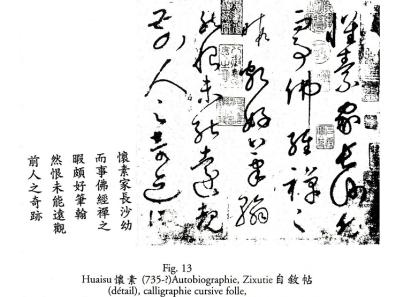

The fig. 13 represents the beginning of the Autobiography of Huaisu in crazy cursive calligraphy. Considered one of the geniuses of cursive calligraphy, Huaisu recounts in this masterful piece his apprenticeship, and particularly his encounter, during a stay in the capital Luoyang, with the calligraphies of Zhang Xu (658 - 748), also a great, exuberant and passionate Tang master whom history has remembered for his achievements in "mad" cursive, kuangcao.

Below is a translation of the passage reproduced:

"[I], Huaisu, a native of Changsha, have worshipped the Buddha from an early age. When prayers and chan [practice] [gave me] free time, I enjoyed [indulging in] calligraphy. It was a great regret [for me] not to have been able to admire the wonderful manuscripts of the ancient [masters]."

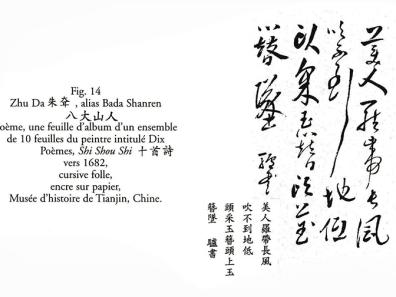

Descendant of the imperial Ming family, Bada Shanren became a monk after the Manchu invasion of China in 1644. From then on, he devoted most of his time to painting and calligraphy. Often considered an eccentric, he was at the origin of a monochrome painting movement of rare vitality, whose influence can be felt to this day.

The calligraphy page in fig.14 corresponds to a poem composed in crazy cursive, kuangcao, by the author around 1682, whose translation follows:

"The beautiful girl wears a long silk ribbon.

The wind blows but fails to make it touch the ground. When she stoops to pick up the daylily,

her jade-embellished hairpin falls to the ground."

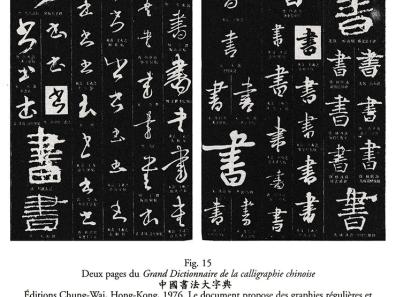

The last illustration we offer (fig. 15) is a two-page reproduction of a work dear to calligraphers, collectors and lovers of Chinese calligraphy. This is the Grand Dictionnaire de la calligraphie chinoise which represents a colossal work of compilation. The authors have researched, collected and assembled, one by one, the multiple spellings of 4,392 characters as they appear on pieces (steles, stampings of vanished steles, horizontal and vertical scrolls, colophons of paintings, various fragments - in all, almost 750 works have been used) throughout history and various collections. They then classified them, patiently collating and editing them to present them in the order of the Chinese dictionary, which arranges characters by "key" (214 in all). In so doing, they have made available to the general public an incomparable reference tool, enabling one to study and appreciate at a glance how the great masters (360 calligraphers are involved) treated a given character in a given style. A very useful exercise for the student would be to identify on these two pages the different styles of the "calligraphie[r]" character, shu, by comparing it with the examples proposed in this presentation.

.

André Kneib, lecturer in Chinese language and calligrapher.

Communication at the Sorbonne Chapel, Paris, 1998

Bibliography

André Kneib and the art of Chinese calligraphy, Stephen J. Goldberg, 2019, Paris, Meroe. 192 pages. ISBN: 979-10-95715-09-2

Notes

[1] Consult Jean-François Billeter's essential work:

Essai sur l'art chinois de l'écriture et ses fondements, Allia, Paris, 2010, 414p.

[2] For pieces held in France at the Musée national des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, consult: Lefeure, Jean A., Collections d'inscriptions oraculaires en France, Institut Ricci, Taipeh Paris-Hong-Kong, 1985.

[3] Cf. Vandermeersch, Léon, Wangdao ou la voie royale, École Française d'Extrême-Orient, vol. CXIII, Paris, 1980, tome Il, pp. 300-301.

[4] Cf. Chavannes, Édouard, Les Mémoires historiques de Se-ma Ts'ien, Adrien Maisoneuve, Paris, 1967, Tome second, p. 550.

[5] Cf. Chen, John T.S., Les Réformes de l'écriture chinoise, Mémoires de l'Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, P.U.F., Paris, 1980.

[6] For a translation of the inscription, cf. Chavannes, Les Mémoires historiques, op. cit., pp. 551-553.

[7] For a transcription of the text and an annotated translation, see Acker, William, R.B., Some Tang and Pre-T'ang Texts on Chinese Painting, Hyperion Press (reprint), Wesport, Connecticut, USA, 1979, pp. LIII-LXII.

.