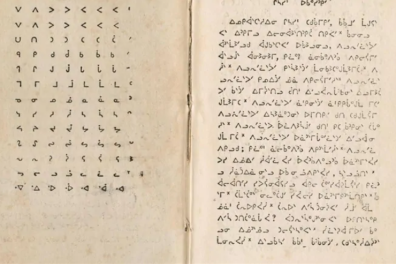

The syllabic script of Inuktitut, the language of the Inuit of the Canadian Eastern Arctic

Writing is a fairly recent phenomenon among most Canadian Inuit. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was only present in Labrador, where Moravian missionaries of German origin had introduced a Latin writing system (very similar to the one they had introduced in Greenland).

From 1855, two Wesleyan missionaries, John Horden and Edwin A. Watkins, introduced to the Inuit of southeast Hudson Bay the syllabic writing system that James Evans had invented in the 1830s-40s to transcribe Ojibwe and Cree (two languages of the Algonquian family).

Evans apparently drew his inspiration for this system from shorthand. But Cree oral tradition postulates a purely aboriginal origin: in the 1830s, a Woodland Cree named Calling Badger is said to have brought back from the spirit world pieces of birch bark bearing the symbols of syllabic writing.

In any case, Horden and Watkins revised this writing system in 1865 so that it better transcribed Inuktitut. Imperfections remained: vowel length, the distinction between certain consonants (i.e. /k/ ~ /q/, /ɣ/ ~ /ŋ/) and the final consonant of closed syllables were not represented.

But this system was easy to learn, and another missionary, the Reverend Edmund J. Peck, greatly favored its use. Preaching the Gospel on the east coast of Hudson Bay and south of Baffin Island for almost thirty years (1876-1905), he transcribed the Moravian texts into the new script, and taught the Inuit to read and write. Those who had learned to use the script from him taught it to their parents, neighbors and children.

It thus spread throughout the Canadian Eastern Arctic (with the exception of Labrador, where the Moravian Latin script persisted).

Here's what Danish archaeologist Therkel Mathiassen wrote about the Inuit he met north of Baffin Island during the fifth Thule expedition (1921-24): "Peck's syllabic writing has spread widely among the Iglulik Eskimos, where mothers teach it to their children, who teach it to each other; most Iglulik Eskimos are able to read and write this rather simple but rather imperfect language, and they often send letters to each other; notebooks and pencils are therefore in great demand among them. "

One thing seems to have appealed to the Inuit about syllabic writing: the signs of which it is composed, when laid down on paper, are reminiscent of the footprints left by animals in the snow. This gives rise to an analogy between writing and hunting: just as we follow footprints to catch game, we follow syllabic signs to grasp meaning. The base atuar(si)- means both 'to read' and 'to follow'.

By the late 1920s, most Inuit in Canada's eastern Arctic knew syllabics without having been to school. Over the following decades, they continued to use it for private correspondence, to take short notes, and to read the religious texts that churches printed.

In the 1950s and into the early 1960s, the Canadian federal government believed that syllabic spelling would eventually disappear due to its imperfections. Linguists were commissioned to develop a rigorous Latin orthography for Inuktitut. This spelling had no effect on Inuit practice. They had not been consulted, and their attachment to syllabic spelling was strong.

With the arrival of the telephone in the early 1970s, the use of syllabic writing in interpersonal communication began to decline. But the 1970s also saw the beginning of the teaching of Inuktitut in elementary school. The idea of standardizing writing had also gained ground. In 1973, Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (now Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami), the national association of Canadian Inuit, began working with Inuit and linguists to perfect the syllabic transcription system for Inuktitut, notably by adding diacritical marks. In 1976, a standard spelling was adopted by the general assembly of the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada. This spelling is still used to transcribe Inuktitut in Nunavut.

It comprises 3 series of 15 main signs and 15 diacritical signs (60 signs in all):

https://tusaalanga.ca/node/2506

During the 1980s, the Inuit of Nunavik decided to deviate slightly from this standard. The version they use comprises 4 sets of 14 main signs and 14 diacritical signs (70 signs in all):

https://nunavik-ice.com/en/c/inuktitut-en/inuktitut-syllabics/#

While syllabic writing is ubiquitous in documents published in Inuktitut in both Nunavut and Nunavik, these are generally translations from English or French, rarely read and often illegible. As for interpersonal communications via the Internet, syllabics are hardly ever used. More generally, Inuit don't write much spontaneously in Inuktitut.

In the early 2010s, the desire arose to unify the spelling practices of all Canadian Inuit. In September 2019, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami adopted a set of Latin characters - Inuktut Qaliujaaqpait - as the transcription medium for all dialects. The syllabic writing of Inuktitut will not disappear, however. Many Canadian Inuit are still very attached to it. It is one of the symbols of their identity.

Marc-Antoine MAHIEU

Lecturer in Inuktitut language and linguistics.

Bibliography

Harper, Kenn. 1985. "The Early Development of Inuktitut Syllabic Orthography." Études/Inuit/Studies 9: 141-162.

Mathiassen, Therkel. 1928. Material Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 6, 1. Copenhagen, Denmark: Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition.

Patrick, Donna, Kumiko Murasugi & Jeela Palluq-Cloutier. 2018. "Standardization of Inuit Languages in Canada." In Pia Lane, James Costa & Haley de Korne (ed.), Standardizing Minority Languages: Competing Ideologies of Authority and Authenticity in the Global Periphery, 135-153. New York, Routledge.

Simon, Mary. "Inuktut Qaliujaaqpait - the product of history and determination." Nunatsiaq News, Sept. 30, 2019: https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/inuit-qaliujaaqpait-the-product-o…

Stevenson, Winona. 2000. "Calling Badger and the Symbols of the Spirit Language: The Cree Origins of the Syllabic System." Oral History Forum 19: 20-24.

Therrien, Michèle. 1990. "Traces on snow, signs on paper. Significations of the imprint among the Nunavimmiut Inuit (Arctic Quebec)."