Integrating history into a Korean as a foreign language (CLO) class - the case of the Korean School of Paris

1. History and state of the art of teaching Korean abroad

Research in the relevant field accelerated[1] , particularly in the early 2000s with the rapid increase in the number of foreign learners of Korean thanks to economic development, as well as the stabilization of South Korea's political regime. In addition, multiculturalism has gradually taken hold in Korean society due to the sharp increase in foreign workers and international intercultural marriages, leading to the need to build Korean language education adapted to this population. On the external front, the number of Koreans living abroad has increased (7.5 million in 2019), making it necessary to learn the Korean language and culture in order to pass them on to younger generations. Thus, the teaching of CLE has developed in relation to Korea's internal and external changes.

Now, CRE (formerly chaeouedongpo / 재외동포) targets three categories of audiences: foreign learners, children from mixed (multicultural) families residing in Korea, as well as Koreans residing abroad and their descendants. In particular, sociolinguistic-didactic studies on the teaching of CLE to CRE learners rapidly established themselves as a field in their own right around the year 2000, and we have been referring to the teaching of Korean as a heritage language (CLO) ever since. This is based on the notion of "heritage language (HL)" proposed by Valdès (2000) and taken up by Cho (2014: 402), as a language less mastered than the dominant language, marked by its marginality and minority tendency; it is neither a mother tongue, nor a second language, nor a purely foreign language.

2. The Korean School

The Korean School has a total of 1,790 establishments worldwide. It is a non-profit, non-governmental organization that plays a dual role as a center for Korean language education abroad and as a representative of the Korean community. It brings together the descendants of Korean immigrants, enabling them to preserve the Korean language, culture and identity. Despite their considerable place in the teaching of CLO, Korean Schools remain in a relatively deficient context due to financial problems, such as lack of classrooms and equipment.

The Korean School of Paris, our research field, has the longest history among the 13 Korean Schools based in France. In the 2020-2021 school year, a total of 135 students were enrolled, including 101 from mixed French-Korean couples, 34 from Korean families and 5 students from French families with no blood ties to Korea. The school primarily offers pupils in cycles 1 to 4[2] the opportunity to learn the Korean language and culture, but also aims to promote intercultural development between France and Korea, and to train long-term world citizens (from the Korean School of Paris website).

With regard to education at the Korean School in general, CLO didacticians criticize, most often, the lack of programs, teaching resources and textbooks adapted to the plurality of students, i.e., dual culture and bilingualism, as well as the heterogeneity of their profile (level in Korean language, age, family situation, objectives and motivations).

There is also a strong imbalance between the skills targeted by the courses: linguistic competence and socio-cultural competence. CLO teaching generally focuses on learning lexis and grammar, neglecting the development of students' socio-cultural and intercultural skills, which can be achieved through learning about culture and history. This tendency to dissociate language and culture is also noted in the speech of the director of the Korean School of Paris: "[...] It's not an official school, but an educational institution for Koreans living abroad that aims first and foremost to learn the language. Afterwards, if possible, we can integrate history and culture as content".

The teaching of CLO thus prioritizes the development of language competence, showing that the methodology of this teaching is still based on the traditional approach instead of adapting a communicative approach and an action-oriented perspective that emphasize learners' know-how and savoir-agir. However, as we have seen from the definition given by the government law on the Korean School, it is a place that teaches the Korean language, culture and history.

Furthermore, according to the regulations drawn up in 2003, the aim of teaching CLO is also to "strengthen the competence, right and interests of Koreans residing abroad on the soil of their country of residence" (Park, 2008: 25). The aim is therefore not only to provide students with language skills, but also to guide them towards a better representation of themselves and their country of origin, thanks to an understanding of Korea through learning about its culture and history. The teaching of CLO thus offers a genuine encounter with the Other for RCEs born and raised in an environment other than Korea. This experience of otherness also enables students to foster the relationship between the culture of their country of residence and Korea, to reconcile themselves with their dual culture, their mixity, and to reflect on and legitimize their plurality.

3. Why teach history?

To answer this question, we need to return to epistemological thinking in order to shed light on the relationship between language and history. In the field of language didactics, history is rarely given its own place. Some research does exist, but it tends to focus on the teaching of History as a non-linguistic discipline (DNL), particularly in the context of an international section - an area that has received very little attention (Duverger, 2011: 10), and very little in the field of foreign language teaching (Koulmann, 2018) or heritage languages. However, language and history present a close relationship worthy of study, as both join the process of cultural and identity reconfigurations that language didactics aims to achieve (Spaëth, 2017).

History as the teaching of culture and civilization in a language classroom

Language teaching methodology is evolving in order to develop learners' linguistic competence and cultural, intercultural and co-cultural competences for deep inter-comprehension with the Other. It is with this in mind that the notion of culture in language learning should be considered as a means of appropriating the shared practices of native speakers. According to Beacco (2000: 157), "all language teaching/learning is thus related to other behaviors, other beliefs, rhythms and habits, other landscapes, other memories". Language teaching therefore necessarily requires a cultural dimension to meet learners' need to know and appropriate the culture relating to the target language. So, while language and culture are interdependent, they are also interchangeable.

As far as history is concerned, it doesn't just refer to knowledge, it also enables us to grasp the evolution of a culture over time. It helps us to understand society by adding the notion of the past, i.e., the evolution of populations in this society, from the past to the present, by building a collective memory. History is thus closely linked to culture.

The notion of culture is often confused with that of civilization. Civilization as a set of cultural practices has often been neglected in language teaching. In this way, by exploring the notion of civilization and its value, it is possible to shed light on the place of History in language didactics, for like civilization, History is concerned with the evolution of a society. From a historical point of view, we could integrate the notion of cultural history to legitimize the relationship between history and culture. This current of historical research aims to study "all the collective representations specific to a society" (Ory, 1987: 68). The aim is to understand history as the combination of a society's imagination and the shared savoir-vivre of an era. It would therefore be interesting to understand the notion of History in the teaching of culture from the angle of cultural history.

In Korean didacticians (Park Kab-su; Jin Dae-yeon), the need to teach culture in CLE has already been claimed. For true communication in Korean, learners need to master not only semantics and syntax, but also culture and sociology. History, representing the evolution of a society, can become a tool for deepening their knowledge of the life and culture of Korean speakers. Ultimately, combining the linguistic, cultural and historical aspects of a language is necessary if learners are to master its use and be able to communicate and act through it.

Identity, language and History

According to Charaudeau, "language is not the whole of language" (2001: 343), it represents the culture, mores, thoughts and habits of the people who speak it. We therefore need to be aware of the discourse of language, of the "ways of speaking of each community" that are the bearers of culture. Linguistic identity is therefore distinct from discursive identity (ibid.: 343). Sharing the same discursive identity means sharing the same mores, the same customs. It is the discursive community that generates cultural identity by sharing the same thoughts, values and representations that are attributed to the use of a language. In this way, language, as the bearer of culture, or rather its use, contributes to the construction of cultural identity. It is therefore a vector of identity. Moreover, language invites us, through communication, to "the mediation of the Other" likely to lead to the discursive formulation of identity (Abdallah-Pretceille, 1986: 307).

For its part, History conveys an individual's attachment to his or her group, and the formation of collective identity through History is well known. History is thus also a vector of collective identity, guiding an individual to find a group of people who share the same past as him or her. From this perspective, teaching Korean history to Franco-Korean students is close to this process of transmitting the collective memory that awakens Korean identity. Our course aims to transmit History in the form of a collective memory in which students will gradually recognize their Korean identity.

Despite this theoretical approach, which explains the place of History in language learning, research on this discipline remains marginal. It has yet to be put into practice. Below are methodological approaches to this teaching through historical elements integrated into two CLO textbooks as well as a Korean History textbook for CRE.

4. How to teach history? - The place of History in the COL textbook: practice and methodology

The need to create COL textbooks has begun to be claimed in some Korean Schools, particularly those in the USA which cater for a large number of Korean-American students. The following extracts are taken from two CLO textbooks, produced with the support of Korean government institutions (Korean Ministry of National Education, National Institute of International Education), as well as that of the International Korean Education Foundation, which contains elements of Korean history. The two textbooks presented here are the first to have introduced History into CLO teaching in 2015. In particular, the Korean for Koreans Living Abroad textbook was reissued in 2020.

4.1. Example 1: Korean for Koreans Living Abroad, 6-2 (재외동포를 위한 한국어, [2015]2020)

Fig.1 : Cover of Korean for Koreans Living Abroad, 6-1 and 6-2 © 2020, Korean Ministry of National Education.

The Korean for Koreans living abroad textbook consists of six volumes, each comprising two volumes. The final volume (6) of the book is aimed at teenagers with advanced Korean.

The textbook is developed along several thematic axes. The first chapter of book 6-2, "World Culture and History", deals with the cultural and historical elements of Korea, as well as those of other countries. The last two units of the chapter: 3. Days and events that changed the world and 4. My Role Models, are devoted to history. The teaching method is based mainly on comparing Korean events and historical figures with those of other countries around the world, to demonstrate cultural diversity and interculturality. By exploring the relationship between Korean and world history, their differences, crossovers and diversity, learners can develop their intercultural and co-cultural competence, enabling them to understand, act and live with the Other. This leads to an understanding of otherness and the formation of global citizens in students.

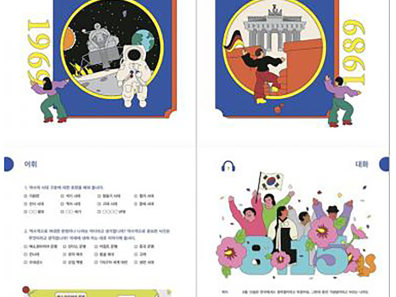

Fig.2-1: Excerpts from Unit 3: Days and events that changed the world in Korean for Koreans living abroad (p.40-43) © 2020, Korean Ministry of National Education.

- Unit 3 consists not only of a presentation of historical events in Korea, but also aims to expose the evolution of the world and society through the defining moments of world history. In the excerpts from Unit 3, images illustrate the first step on the moon in 1969, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, or the birth of civilizations in different geographical areas (Fig.2-1).

- This timeline shows important events in world history, from Christopher Columbus's first voyage to America in 1492 to the present day. It also includes the Korean War (1950). By comparing elements from world history with those from Korean history, students gain a better understanding of themselves and the Other, and reconfigure their self-image. This is a feature of intercultural education and otherness (Fig.2-2).

Fig.2-2: Timeline of world history in Unit 3 of Korean for Koreans living abroad (p.48) © 2020, Korean Ministry of National Education.

Similarly, Unit 4 compares major historical and cultural figures from Korea with those from other countries (Fig.2-3).

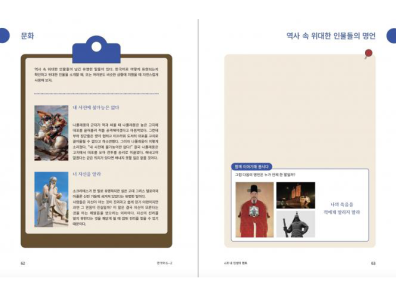

Fig.2-3: Excerpts from Unit 3 in Korean for Koreans Living Abroad (p.62-63) © 2020, Korean Ministry of National Education.

In the same way, Unit 4 compares major historical and cultural figures from Korea with those from other countries (images below).

4.2. Example 2: Adapted Korean - for Koreans living in French-speaking countries (CM1 and CM2) tome 5, 6/맞춤 한국어 5, 6 - 프랑스어권, 2012)

Fig.3 : Cover of Coréen adapté, - pour les Coréens résidant dans des pays francophones (CM1 et CM2) tome 5,6 © 2012, Korean Ministry of National Education.

This manual is aimed at children and teenagers of Korean origin living in French-speaking countries. Volumes 5 and 6 correspond to CM1 and CM2 pupils, who are enrolled in their local Korean School and have an advanced level of Korean.

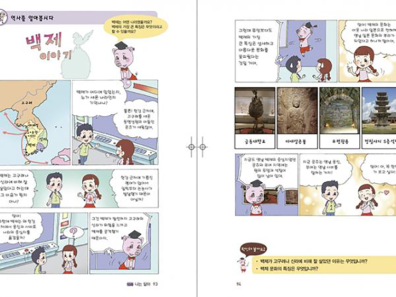

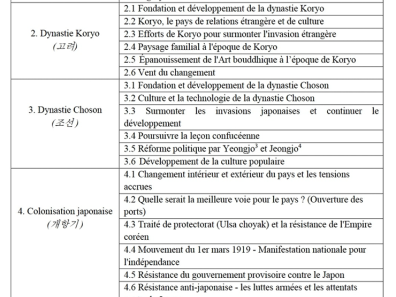

The unit is made up of 8 parts, the first six of which aim to develop the four language skills equally: oral and written comprehension, oral and written production. The last two parts alternate between culture and history. The section entitled "Let's Learn History" presents Korean history chronologically, from antiquity to the present day. Volume 5 provides information on Korean history from prehistoric times, followed by the kingdoms of Gojoseon, Goguryeo, Baekje, Silla and Balhae. The final volume focuses on the history of the Goryeo and Choson kingdoms, followed by the Japanese occupation and contemporary times. This part is presented in the form of comic strips showing dialogues between two children.

This is a tool that encourages students to learn history and interact in the classroom. The table below shows the historical elements inserted and presented in these two books.

Table of contents for volume 5, 6.

Examples: extracts from "Apprenons l'Histoire" from the textbook Volume 5 (Korean Ministry of National Education, 2012: 25-26 93-94)

Fig.4-1: Extracts from Unit 2 of the textbook Volume 5: "Apprenons l'histoire" History of the Dolmen (p.25-26) © 2012, Korean Ministry of National Education

Fig.4-2: Excerpts from Unit 10 of the textbook Volume 5: "Let's learn history" History of the Paekche Kingdom (p.25-26) © 2012, Korean Ministry of National Education

Examples: excerpts from "Let's Learn History" from the textbook (Volume 6) (idem: 61, 113-114, 129)

Fig.5-1: Excerpt from Unit 6 of the textbook Volume 6: "Let's Learn History" Kings of the Choson Dynasty (p.61) © 2012, Korean Ministry of National Education

Fig.5-2: Excerpts from Unit 12 of the textbook Volume 6: "Let's learn history": Korean War (p.113-114) © 2012, Korean Ministry of National Education

To integrate History (Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Modern Era), which includes difficult lexicons, the manual has chosen the playful form (the comic strip). The use of multimedia resources, such as drawings and photos, can promote the understanding of History and its accessibility.

Fig.5-3: Extract from Unit 14 of the textbook Volume 6: "Let's learn history": Koreans living abroad and the multicultural family (p.129) © 2012, Korean Ministry of National Education.

In Unit 14 of Volume 6, the "Let's Learn History" section presents the history of Koreans living abroad within a multicultural family. Although CLO's manuals are aimed at audiences from the Korean diaspora, its presence in this book is relatively marginal. Above all, the textbook seeks to convey the Korean national identity. On the other hand, the inclusion of the Korean diaspora in the teaching of COL is essential so that students can construct a better representation of their identity as CRE. In this way, they can also encourage cultural mixing and legitimize their plurality. This initial presence of elements on the Korean diaspora is therefore encouraging.

These two examples of CLO textbooks show the beginning of the presence of History in CLO textbooks. However, the teaching of history is still relatively limited. It is not accessible to everyone, as history is generally only included in these textbooks for cycle 3-4 students with an advanced level of Korean. This subject appears as an additional content in the textbook, simply to enrich and complete the cultural component (particularly in the first textbook). While its position remains secondary, this phenomenon is nonetheless encouraging, as these textbooks now emphasize interculturality and diversity through history, while achieving the goal of learning Korean.

Despite these efforts and considerable improvements, few Korean school teachers actually use these textbooks in their lessons. In this respect, some CLO trainers believe that these textbooks are ill-suited to the linguistic, cultural and identity plurality of the students. According to the director of the Korean School of Paris, trainers tend to prefer the textbooks used in Korea, even though the quality of these two works is often judged insufficient to provide satisfactory teaching in line with parents' expectations. For the former director of the Korean School in New York, the textbooks in question were never used during her tenure, as she considered them unsuited to the mentality/sensitivity and linguistic and cultural competence of the students. It was against this backdrop that Korean schoolteachers and teacher-researchers specializing in CLE/CLO began to stress the need to create new textbooks focusing on Korean history and culture, better adapted to the linguistic level and cultural and identity context of child-adolescents from CREs. In response to this demand, a government project "Creation of the History textbook for Koreans living abroad" was launched.

4.3. Example 3: Understanding Korea (2016) and Understanding and History of Korea (2019, planned publication in 2022)

As a result of this project, two history textbooks were created: Understanding Korea (2016) and Understanding and History of Korea (planned publication in 2022). This article is particularly concerned with the second book and research into teaching practice and modality in order to integrate this book into CLO courses.

Fig.6: Cover of the textbook Understanding Korea © 2016, Korean Ministry of National Education.

Compared with the first volume, which presents Korean history along thematic lines, Understanding and History of Korea offers in-depth learning of history in a chronological and general way. It corresponds to the advanced CLO class, for teenagers in Cycle 4.

Table of contents of the Understanding and History of Korea textbook (publication scheduled for 2022)

The manual focuses on the development and attachment to identity of Korean students living abroad. On the one hand, the teaching of Korean history enables them to recognize Korean identity and make it their own; on the other, it leads them to experience diversity, from different points of view, and enables them to acquire the values of world citizens.

The book also incorporates a playful, interactional approach. Creative activities such as games, discussion and writing are just as important as the descriptive content. The manual even includes a "Workbook" with activities associated with each unit. This playful form aims to increase student motivation and facilitate the acquisition of historical knowledge.

Fig.7: Carrying out the activities in the Korean history textbook in CLO class © 2020, Jiye Seo

In addition, the intercultural approach is particularly emphasized in this manual. Aimed at students in contexts other than the Korean setting, the book attempts to show and value cultural diversity, and to nurture cultural interaction through exercises/activities.

Examples.

1. Activity on the founding myths of each country

2. Reading exercise, comparing the traditional masked theater of each country.

3. Comparison of movements and characters who resisted colonization by imperialist countries in Asian countries.

These intercultural activities based on comparatism offer students experiences of otherness and cultural diversity, and convey universal values such as tolerance and peace.

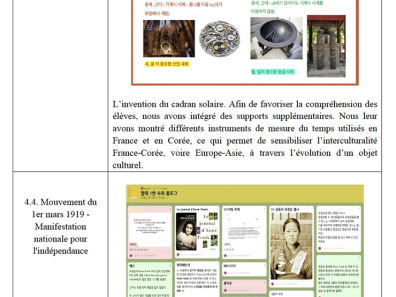

In addition to comparatism, the cultural transfer method, can be applied to address interculturality and cultural diversity in the teaching of History. The notion of cultural transfer is first and foremost a historical method, based on the fluidity and transnational nature of culture. It emphasizes "a movement of objects, people, populations, words, ideas and concepts between two cultural spaces", and focuses on the process of cultural cross-fertilization (M. Espagne, 1999: 286, quoted by B. Joyeux-Prunel, 2003: 152). In order to strengthen the France-Korea intercultural relationship and foster the cultural and identity fusion of Franco-Korean students, the course can be built on this cultural transfer method.

The methodological approaches we have constructed and used to integrate them into the Korean School of Paris are as follows:

- The various activities, dialog texts, multimedia teaching materials and authentic documents (films, videos, news reports, etc.) stimulate students, creating a taste for history.

- The comparison between French and Korean history motivates students, helping them to understand concepts and lexicons, enabling them to grasp the evolution of the two societies (the diachronic flow of two histories) in parallel. In particular, the treatment of the same historical period in the history course at the Korean School and in French schools encourages their acquisition of historical knowledge. In addition to comparatism, the cultural transfer method can be implemented in the integration of history in CLO. In this way, the course can promote interculturality and Franco-Korean métissage.

- The treatment of sensitive subjects, the use of the emotional register as well as visits to historical sites are pedagogical means that energize the learning of history through empathy. These three teaching methods enable students to appropriate history as a collective memory and not simply as historical knowledge. However, a critical vision and a cautious attitude are needed towards these empathy effects so as not to create feelings of hostility towards the Other.

5. Effects and expected benefits of integrating historical elements into the CLO course

Many effects emerge after this experimentation and didactic observations in the teaching of history in CLO:

- From a purely linguistic and practical point of view, learning history develops learners' literacy competence (reading comprehension/written production) in the target language, through reading the text and/or writing.

- Integrating history into the language classroom can also promote the goals that the didactics of this discipline seeks to accomplish. These include critical thinking and argumentative skills through debates organized in class.

- History joins the teaching of culture and civilization, leading learners of a language to grasp the mores, representations, thoughts and shared memory of the speakers of that language. It offers learners the opportunity to encounter the Other, to recognize and respond to their differences. In this way, the integration of history links up with the intercultural education and otherness that language teaching aims to achieve today.

In the final analysis, history in a heritage-language Korean class is, of course, a tool for learning Korean language and culture, but not the only one. By adopting an intercultural, plural or cultural transfer approach, this course can also become a mediator between past and present, Korea and France. In this way, teaching the history of the country of origin is the common thread that leads students towards a harmonious fusion of identity, a cohesion between two cultural contexts.

6. Limitations and difficulties

Despite these positive effects of integrating history into CLO, it is still difficult to implement this teaching in most Korean Schools. The constraints are many.

Firstly, the mismatch between students' Korean language proficiency and the level of the textbook is one of the biggest obstacles facing Korean School teachers. The difficulty of understanding the historical lexicon can easily demotivate students from learning Korean history. The second difficulty concerns time management. It's difficult to organize a history class and a language class in parallel, as the Korean school only allows for three or even four hours per week. In addition, there are obstacles relating to the contextualization of textbooks and teaching aids.

Although the textbooks outlined above tend to adapt to the students' context by drawing on the intercultural and communicative/actional approach, they contain certain dissonances, and above all, they present methodological limitations in the way they address the cultural and identity diversity of the CRE.

7. Suggestions for improvement

In order to overcome these challenges, several approaches can be considered.

- External efforts: 1. Support from the South Korean government for the development of Korean language teaching, such as the creation of textbooks and teaching aids, the development of multimedia resources. 2. Exchanges between didacticians/linguists in Korea and France on didactic methods for teaching Korean language and culture. 3. Cooperation between specialists in the field, including researchers in France. Within this framework, new Korean textbooks can be created.

- Internal efforts: 1. Epistemological reflection on the notion of culture and history in language learning. 2. Awareness of the lack of cultural and historical elements through analysis of current CLE/CLO textbooks. 3. The content and integration of history as part of intercultural and pluralistic education, and appropriate activities. 4. In-depth understanding, attention to students' contexts and psychological and cognitive characteristics, awareness of their linguistic, cultural and identity plurality, which sometimes provokes a strong confrontation in them.

Despite the difficulties encountered in recent years, the Korean School of Paris does its utmost to offer the best teaching to students wishing to learn the language, culture and history of Korea. What's more, the integration of history not only concerns the teaching of CLO, it can also open up and enrich a new cultural/intercultural strand in the teaching of Korean as a foreign language aimed at French learners.

Jiye SEO, Master 2 (M2) graduate in Didactique des langues (DDL) at Inalco

Bibliography

ABDALLAH-PRETCEILLE, M. 1986. Vers une pédagogie interculturelle. Paris: Anthropos.

BEACCO, J-C. 2000. Les Dimensions culturelles des enseignements de langue. Hachette Français Langue Étrangère / Kindle Edition.

CHAREAUDEAU, P. 2001. "Language, discourse and cultural identity". In Éla. Études de linguistique appliquée, n°1213-124. p. 341-348.

CHO, T.R. 2014. "Analysis of Korean Language Curricula for Overseas Koreans from the Aspects of Heritage Language Education: Focused on the general theory". In Bilingual Research, vol. 55. p. 381-407.

DUVERGER, J, coord. 2011. Enseignement bilingue - Le professeur de Discipline Non Linguistique : Statut, fonctions, pratiques pédagogiques. Paris: ADEB - Association pour le Développement de l'Enseignement Bi/plurilingue.

JIN, D-Y. 2016. "Instructional Design for Teaching Korean History and Culture as a Foreign Culture". In The Education of Korean Language, 38(0), pp. 223-252.

JOYEUX-PRUNEL, B. 2003. "Les transferts culturels: Un discours de la méthode". In Hypothèses, 6. p. 149-162.

KOULMANN, A. 2018. "L'enseignement de l'histoire de France en Français Langue Étrangère", In Education and plurilingual societies. [Online]. p. 44-55, online February 08, 2019, accessed May 01, 2019,

URL: http://journals.openedition.org/esp/2318

ORY, P. 1987. "L'histoire culturelle de la France contemporaine: question et questionnement". In Vingtième Siècle, revue d'histoire, n°16 October-December. Dossier: L'Allemagne, le nazisme et les juifs. p. 67-82

PARK, K. 2008. "Status and specific measures of Korean education for Koreans living abroad through the Korean School, 한글학교를 통한 재외동포 한국 교육의 현황과 대책". In New Korean Language Fashion / 새국어생활, vol.18, no.3. p. 23-39.

SPAËTH, V. 2017. "History, historicities in language didactics", In Journée d'études, Paris, [Online] uploaded December 2017, accessed November 18, 2021,

URL: https://calenda.org/405666

CLO Handbook

KIM, J et al. [2015] 2020. Korean for Koreans living abroad, 6-2 / 재외동포 한국어 6-2, [2015] and in 2020. Seoul: Ministry of National Education

KANG, S et al. 2012. Adapted Korean - for Koreans living in French-speaking countries (CM1 and CM2), volumes 5 / 맞춤 한국어 5 - 프랑스어권. Seoul: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology

KANG, S et al. 2012. Adapted Korean - for Koreans living in French-speaking countries (CM1 and CM2), volumes 6 / 맞춤 한국어 6 - 프랑스어권. Seoul: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology

JEONG, M. publication expected in 2022. Korean Understanding and History - Deepeningt / 한국의 이해와 역사 - 심화. Seoul: National Institute of International Education.

JEONG, M. 2017. Understanding Korea - Initiation / 한국의 이해 -입문. Seoul: National Institute of International Education.

Sitography

Korean School of Paris. [Online]. http://ecolecoree.korean.net/ecbbs/

Fondation des Coréens résidant à l'étranger. Studykorean. [Online]. http://study.korean.net

Notes

[1] This work stems from research carried out with a class of French-Korean middle school students at the Korean School of Paris, as part of my M2 Didactics of Languages, from which some results are drawn.

[2] Cycle 1: cycle d'apprentissages premiers (petite, moyenne et grande sections de maternelle).

Cycle 2: cycle des apprentissages fondamentaux (CP, CE1 et CE2).

Cycle 3: cycle de consolidation (CM1, CM2 and sixième).

Cycle 4: cycle des approfondissements (cinquième, quatrième and troisième).

[3] Yeongjo (1694-1776) was the twenty-first king of the Choson dynasty.

[4] Jeongjo (1752-1800) was the twenty-second king of the Choson dynasty.

[5] Yu Kwan-sun (1902-1920) was a symbolic figure of the March 1, 1919 resistance movement against Japanese colonization, who died as a result of Japanese torture. She is considered the "Joan of Arc of Korea", the national heroine who gave her life for the homeland.