Llacan databases

Databases are highly prized research tools because, by organizing data in a structured way, they enable filtering, for example to isolate a particular sample, or more or less complex searching of these data and quantification of results. Here are a few illustrations of this at LLACAN.

Databases tooling

Researchers at the laboratory LLACAN (Language, Languages and Cultures of Africa), are linguists committed to the description of African languages, more specifically, little-described languages. As soon as access to personal computers began in the 80s, researchers were confronted with the difficulty of managing their textual data with word-processing software. With character encoding limited to 256 codes, they had difficulty entering data requiring non-Latin characters, such as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

This situation, which lasted for over 15 years, led to the creation of numerous fonts to display these 'exotic' characters, as well as tricks to extend the keyboard's capabilities to easily enter these characters. With the advent of the universal Unicode encoding, followed by a slow progression towards its support by data entry and processing software, this difficulty is no longer an issue, but it remained to manage the researchers' old data.

A database of fonts created at LLACAN, showing the distribution of special characters over the 256 codes of old fonts, ensures the transcoding of old data when it needs to be re-exploited.

A database of the phonological systems and alphabets of 200 African languages, based on Rhonda L. Hartell's Alphabets of African Languages (1993), can be used to visualize the sounds of each language in the traditional phonetic space of consonants and vowels, as well as the characters used to transcribe them in the official orthography of the time. In this way, you can make phoneme or grapheme inventories, by language of the same linguistic group, or by country, or search for languages using the same group of phonemes or graphemes.

.

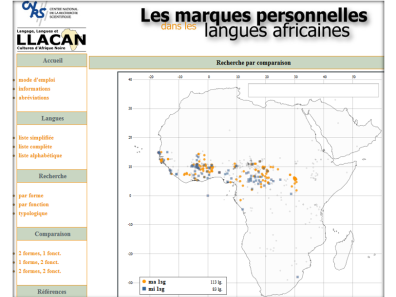

Databases for comparatism

Some research work in comparatism has led to the creation of databases on fairly specific subjects, such as the historical comparative lexicon of the Sara-Bongo-Baguirmian languages or personal marks in African languages. These databases make it possible to concentrate in an organized space information that was previously scattered across multiple works. Filtering and searches can then be used, for example, to compare the spread of a form or function across the geographical space of Africa.

Lexical comparatism

Capitalizing on these different approaches, the idea of designing a more ambitious project that would bring together the different functionalities of these specific tools in a large lexical database, took shape with the creation of the RefLex project, which concentrates all known lexical resources (published or grey) on African languages in a single database. To date, over a million entries are accessible, linked to the PDF documents from which they originate. Data traceability is indeed a specific feature of this tool, as it enables sources to be controlled (access to sources is reserved for registered users to avoid indelicacy).

On the basis of these lexical resources, various modules enable users to make comparisons by selecting sources by geographical or linguistic area, on which they can work. For example, you can search for cognates, i.e. lexemes that potentially have the same origin, by searching for all words corresponding to the same gloss (e.g. horse). The user can then compare (by alignment) the phonemes making up the words in his dataset, and suggest correspondences between sounds from one language to another. The registered user can thus work in his or her own allotted space, on the domain of interest to him or her, and enrich the work of spotting sound correspondences from one language to another, which will make it possible to infer hypotheses of kinship between languages.

Corpus Oraux

Research programs (CorpAfroAs, Sénélangues, CorTypo, CorMand...) focusing on linguistic description are also leading to the creation of textual databases derived from the spoken word. Audio recordings in the different languages studied by project members are archived, and their transcriptions, translations and morpho-syntactic annotations are ingested into a database accessible online. These texts can then be viewed and listened to by the user, who can also search a predetermined set of resources on the basis of the annotations.

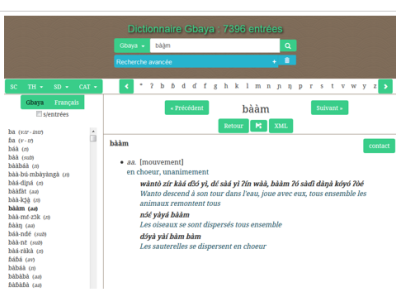

Researchers also use lexical data management tools to build dictionaries over years of research.

.

Databases have become indispensable tools for research, and making them freely available or shared on the internet helps to disseminate the products of LLACAN research, as well as the means of data analysis and validation.

Christian Chanard

Head of LLACAN's IT department