A Quichua storyteller and her repertoire

As part of the master LLCER Oralité discipline at Inalco, I have been focusing on the Quichua oral tradition in Ecuador. Until now, studies of Quechua stories have focused on the interpretation and circulation of narratives, and very few have introduced an ethnolinguistic perspective. Based on the methodological notions of context, performance, situation and mode of communication, ethnolinguistics has triggered a significant amount of work in other geographical areas.

Africanist research into the notion of "textual unity" particularly caught my attention during my training. The tale, which is the subject of my research, is considered in this approach as an element of a larger textual unit. This textual unit can be considered from two points of view: that of the storytelling session (which may include elements of conversation) and that of an individual repertoire. It is on these two levels that I conducted my fieldwork.

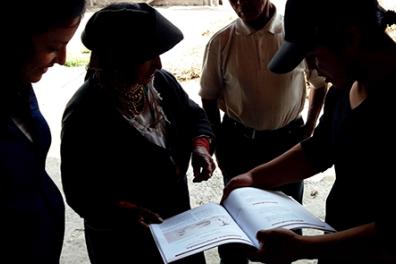

My fieldwork took place in the province of Imbabura in northern Ecuador, between August and September 2016 as part of the preparation for the La tradition orale quichua en Équateur days organized at Inalco[1]. The primary objective of the collection was to prepare with Quichua storytellers[2] M. C. and, her husband, J. A. the performance they would give in Paris during these days. Contact with them was made possible by their daughter, M. D., who, like me, lives in Paris. Part of the material collected in this context forms the corpus on which I'm working. In my work, I describe each storytelling session, including the summary of the tales and the comments made by the storyteller, as well as our conversations. This approach has enabled me to highlight a series of points conducive to making scientific advances in the understanding of Quechua oral literature:

- It is possible to appreciate how the tales are interwoven with fragments of life stories.

- It is possible to hear a Quechua storyteller express himself for the first time on his tales, particularly on the status of the veracity of events reported in stories set in mythical times.

- The description of the context of enunciation per storytelling session also allows us to glimpse a differentiation between daytime and nighttime stories.

The repertoire collected from M. C. consists of 35 oral texts comprising the story of his life and a variety of tales whose range of geographical circulation is local, regional and pan-Andean. M.C. says she learned most of the tales from her father, and she also agreed to tell, at my request, those her husband used to tell and those she heard on the radio or television. Certain themes in her repertoire are recurrent, suggesting that M.C. attaches particular importance to them. These are themes that have a concrete connection with elements in the storyteller's life, such as death. She maintains a close and truthful relationship with the tales, and cultivates a sense of belonging: she recognizes her tales as part of her father's transmission.

The narrator's imprint is perceptible in the transmission of the tales through the description of the context of enunciation of the set of sessions that make up the individual repertoire. This approach shows that transmission involves the storyteller positioning himself in relation to the tales he tells. In fact, he chooses them according to circumstances, preferring certain texts to others. This approach contradicts the idea that oral heritage is immemorial and, being transmitted from generation to generation, is implicitly anonymous.

The training I received in the Master LLCER discipline Oralité, in contact with specialists in the oral traditions of Africa, Asia, the Near East and Eastern Europe, The training I received in the Quechua language enabled me to acquire skills that made it possible to collect, scientifically transcribe and translate into French the repertoire of this Quichua storyteller, thus constituting a unique document for studies of Andean oral tradition[3].

This document is the basis for the current analysis I'm carrying out, as part of my psychoanalysis thesis, on the psychic issues at stake in the transmission of Quichua oral literature in a context of this tradition's erosion. Many Andean tales feature a set of family and social roles, and often recount the protagonist's awareness of the nature of the character with whom he or she is interacting, and of his or her relationship with him or her. According to César Itier, this relationship of otherness can be transposed to the relationship between a storyteller and his audience. One of the challenges of my thesis is to rethink this otherness in the light of the relationship that is woven within a psychoanalytic session, and in turn to think of oral storytelling as a means of renewing the psychoanalytic approach.

Verónica Valencia Baño, PhD student.

Thesis topic: Oral tradition and subjective processes. Le cas d'une conteuse quichua de l'Équateur.

Travail de recherche en codirection Paris 7- Denis Diderot et Inalco.

_______________

[1] These days took place on December 9 and 10, 2016, thanks to the financial support of the Ministry of Culture in Ecuador, the Université Sorbonne Paris Cité (USPC), the Centre d'étude et de recherche sur les littératures et les oralités du monde (CERLOM) and the Institut des Amériques (IdA).

[2] Quichua refers to the Quechua language variant spoken in Ecuador.

[3] This paper is the subject of a forthcoming publication project.