Uyghur: from a lingua franca to an endangered language

The contemporary Uyghur language is spoken by around 15 million people within the Uyghur Region (as a mother tongue for 12 million Uyghurs and as a usage, secondary or school language for 3 million other Turkic speakers) and by around one million speakers in the diaspora. The Uyghur language belongs to the Qarluq group of the Turkic family.

Uyghur is an agglutinative language with a verb-word subject-object order. It respects vowel harmony, which follows fairly consistent rules. Nouns are inflected for number and case, but not gender or definition as in many other languages. There are two numbers such as singular and plural, and mainly six different cases similar to all other Turkish languages. Verbs are conjugated in all tenses, and there are around ten tenses in Uyghur. The basic lexicon of the Uyghur language is of Turkish origin, but due to the different types of linguistic and cultural contact throughout the region's history, many words have been adopted from the Persian and Arabic languages, particularly after the Islamization of the region. Since the 19th century, words borrowed from Russian and Chinese have also played a significant role, particularly Russian in the north of the region. Chinese terms, particularly in political language, became widely used during the Cultural Revolution, but from the 1980s onwards, they were replaced by Uyghur, Arabic, Persian or Russian vocabulary.

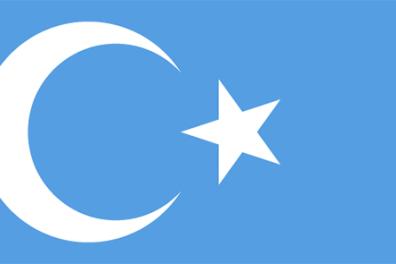

Since the 4th century AD, Uyghurs are said to have used around ten different scripts. Among them, the most important are the Sogdian script (4th-5th century), Orhun or runic (5th-8th century), ancient Uyghur[1] (8th-14th century from the Mongolian plateau to the Uyghur Empire of Qocho), Khaqaniye[2] (10-13th century in the Qarakhanid kingdom), Cagatay[3] (14-20th century from the Chagataid dynasty to the Republic of East Turkestan) and, since the 1980s, Reformed Arabized Uyghur. Since the creation of the autonomous region, the Uyghur script has been changed three times between 1956 and 1984 (M. Zhou, 2003). These repetitive changes to the script of an entire people in such a short space of time testify above all to the State's desire to assert the superiority of another language, in this case Mandarin, by giving orders to change, as it sees fit, the script of a supposedly secondary language. This symbolic violence exerted by the Chinese state on the country's Non-Hans is expressed not only in terms of language, but also in other aspects of social life. But China's language policy in its outlying regions is the most symbolically violent demonstration of this. According to Pierre Bourdieu, the official language is linked to the State, both in its genesis and in its social uses. It is in the process of state-building that the conditions are created for the constitution of a unified linguistic market dominated by the official language. This state language becomes the theoretical standard against which all linguistic practices are objectively measured (Bourdieu, 2001).

All studies and publications on languages in China are carefully managed by linguists from the Nationalities Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, according to sociolinguist Arienne Dwyer, who deplores the fact that all the experts at this institute are both exclusively Hans and male (Dwyer, 1998).

The Uyghur language between 1990 and 2016

If the Uyghur language has survived the changing language policy of the Chinese state since the official colonization of Uyghur territory by People's China, it's harder to say the same now since China's genocidal policy in the region since 2016. Systematic attacks on the use of the language intensified from the mid-1990s onwards: firstly, the banning of higher education in the Uyghur language in favor of Chinese, forcing Turkish and Mongolian students to take a year of preparatory classes before taking a degree at universities in Uyghur country, and two years of preparatory classes for those going to Chinese universities in inland China. In 2000, a new concept was introduced to accelerate the Sinicization of Turkic students: the Xinjiang Class. Here, the best Uyghur and other Turkic middle-school students are selected after their high-school leaving certificate, and sent to study in Chinese high schools in Inner China, in order to distance them from their cultural and linguistic environment and train a new pro-Chinese generation. Studies since 2012 on these classes have shown that this policy has been a total failure (Grose, 2019). That same year, another language policy was imposed under the name of "bilingual education", also creating "experimental classes" in prestigious Uyghur high schools where all subjects are taught in Chinese except Uyghur literature, again choosing the best high school graduates. From the mid-2000s, a new policy aimed to close down Uyghur schools in the name of "combined schools", whereby pupils from Turkic and Mongolian schools leave their now-closed schools to take classes in Chinese schools, again in the name of "bilingual education", while teaching all subjects in Chinese. Integration into the same "linguistic community", which is the product of political domination, constantly reproduced by institutions determined to impose universal recognition of the dominant language, is the condition for the establishment of relations of linguistic domination, as Bourdieu notes (Bourdieu, 2001).

Despite these increasingly linguicidal policies, Uyghurs have not relinquished the lingua franca status of their language; on the other hand, a certain openness is emerging towards Uyghur entrepreneurs active in Uyghur light industry, particularly from 2010 onwards when regional authorities decided to relax economic policy to allow Uyghurs to become a little richer, and thus calm their discontent linked to inequality of opportunity. Although studies show the huge gap between the benefits derived by the Uyghurs and the Chinese (Howell & Fan, 2011), which explains, among other things, the Uyghurs' discontent, some of them have managed to take advantage of it. For example, Uyghur industry, previously confined to the agri-food and IT sectors on a small regional scale, has expanded nationally and even internationally. Uyghur companies have sprung up all over the region, particularly around three regional hubs: the capital Urumchi, the Aksu and Khotan regions in the south of the country.

An ethnic industry has emerged. As a result, it has encouraged cultural fields by promoting the use of the Uyghur language in everyday and public life. Thus, the "Uyghurization" of everyday items has enabled the Uyghur language to reach a national level, even prompting major Chinese banks to issue bank cards in Uyghur and inserting Uyghur into some Beijing ATMs.

In 2015, on her Weibo account, China's equivalent of Twitter, famous Uyghur presenter Munire Ghopur had claimed that Uyghur had officially become the second most widely used language after Mandarin in China. The fact that the Uyghur light industry promotes the use of the Uyghur language in a period when it is being eliminated from school and university use is both a marketing argument and a bonus for strengthening nationalist sentiments.

This situation has changed abruptly since the end of August 2016 and the change in the leadership of the region's Communist Party. Zhang Chunxian gave way to Chen Quanguo, who arrived directly from Tibet after his five years of strict control that made him famous with President Xi Jinping. The new general secretary told the Xinjiang Daily (link in Chinese) on February 21, 2017 that "in Xinjiang, without stability and security, everything is equal to zero".

In "nationalized" societies, particular languages were reduced to survivals, exchanges between the various populations brought together by the nation-state multiplied (Schnapper, 2001). But in the case of the Uyghur language, since 2016, survival itself is not assured, as the Chinese state now rejects the multiculturalism promoting one and only one dominant language everywhere in the colonies.

Where is Uyghur going?

Stability appears to be the watchword for simply eradicating this culture and language far removed from the dominant norm dictated by the Sino-centric state, and almost the entire Uyghur intellectual and industrial class has become the prime target of mass arrests, detained in concentration camps intended for Uyghurs and other Turks. Uyghur schools are all closed down, and the teaching of Uyghur is totally banned in 2017, officially only to authorize a few hours of optional courses in certain schools. Oral use is also banned in the educational environment and at work in certain prefectures. The issue now is human survival for the Uyghur population, who have nowhere to flee, unlike the Kazakhs, Kirghiz or Uzbeks, who each have an independent state on the other side of the border. The process of "assimilation" of populations is part of the logic of the nation-state, which Gérard Noiriel calls the "tyranny of the national" (Noiriel, 1991). In the case of the Uyghurs, who live on their own territory but are subject to the colonial tyranny of a genocidal state, the question now is not the survival of their language, but the very existence of the Uyghur nation that has contributed so much to Asian civilization at large.

Dilnur Reyhan

Sociologist, teacher of Uyghur language, civilization, history and literature, at Inalco .

http://www.inalco.fr/langue/ouighour

[1] This is a vertical script from left to right. It is used today by the Mongols with slight modifications.

[2] During this period, the Uyghurs used the Arabic script, considered to be a sacred script, with little or no modifications.

[3] It is an Arabic script that was here adapted to Uyghur specificities (particularly with regard to sounds and grammatical structures). In addition to the twenty-seven Arabic letters, the alphabet included five Persian letters.